Walmart’s Mega Nudging Test

Walmart partnered with academics whose listing on the published paper reads like the credits on a Hollywood blockbuster movie, which is to say almost as long as the movie.

The aim? Increasing flu vaccination rates in hopes it would provide guidance for increasing Covid vaccine uptake.

This team of social scientists came up with 22 evidence-based messages to boost vaccination rates. The nudge messages were texted to over 700,000 Walmart pharmacy patients last fall and encouraged folks to visit Walmart for a flu vaccine.

There are reams of lessons to be learned for anyone whose job it is to get another human being to do something – i.e. everyone reading this.

The scientists banded together in small teams to devise their different communication strategies relying, as you’d imagine, on theory and evidence to guide their “ideation”.

Lesson One: No blue-sky here. The best innovation comes from understanding, not inspiration or divine intervention.

Lesson Two: Small teams of experts are always better than ‘consensus’ teams of non-experts or hierarchical teams where biggest title opinions win out, or death by committee review.

The messages ranged from interactive (i.e. requesting replies) to informational, some included just one message, others had follow-up texts sent up to three days later.

Each team had their study design, analytical and predicted outcomes preregistered.

Lesson Three: If you don’t specifically state what the outcome of your test will be and why, it’s almost certainly random guessing and should never have donor dollars spent on it.

Lesson Four: If you don’t have an analytical plan to determine if the test won or lost then don’t spend donor dollars testing it. Note: this plan should be more rigorous than eyeballing percentages and ideally more than running a simple bivariate, statistical test. Most of the analysis in the Walmart testing used regression that allows for control variables – e.g. patient age, race/ethnicity, gender.

The teams decided to focus on the population who is not opposed to the flu vaccine rather than the skeptics. They did this by selecting patients who had received the flu shot the prior year. All the messaging was therefore aimed at closing the intention-action gap where we lack sufficient motivation to do what we intend to do.

Lesson Five: People are different. One-size-fits-all is never optimum. Our critique of this work is that it still doesn’t go far enough in getting beyond one-size-fits-all. They did what most do, use what’s available and convenient (e.g. data on who got the shot last year) rather than force themselves to dig deeper into how this population could be further subdivided based on Identity or Personality, for example.

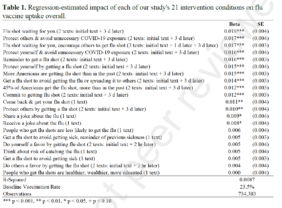

We’ve listed the 22 interventions rank ordered by effectiveness. The top performing message told folks there was a flu shot waiting for them. This is based on the endowment principle and loss aversion. The shot belongs to me. “I don’t want to give it up” because we are much more averse to loss than seeking gain (even if the two are equal). There is likely a sense of reciprocity as you’ve taken the time to set this aside for me, it would rude be or impolite to not take it.

The messages that were more clever or informal – sharing a joke – were less effective

Lesson Six: Context is king. This is a pharmacy as messenger. That invokes a level of formality and seriousness. The tone that matched expectation and situational norms worked best.

“Best practice” is not the winning message, envelope or sequence. It is the process.

Kevin

Kevin