Are You Undermining Donor’s Sense of Control?

People give of time and treasure.

We know this to be true. A factoid in support: Americans donate over $310 billion and volunteer 8.8 billion hours per year.

If you take the median household income in the US (67k) and the average hours worked in a year you see that the hours given are worth more than the direct dollars.

There is plenty of research showing people prefer to give time over money. This is on average, there are folks who are time-poor and find it easier or even preferable to write a check.

But that doesn’t negate the overall time preference. The real question is why? What are the psychological aspects of this time preference and if your organization has little need for volunteers, what can you do to make money the preferred choice or at least on par with the time giving preference?

We’ve tested a time and then money ask and results are mixed but there are occasions when asking for a trivial amount of time first (i.e. sign this petition) and then asking for money creates lift for the latter. This happens because asking for money can light up the same parts of the brain as experiencing physical pain. Yikes.

The ask for time first changes the mental mood, making an easier glide path to a financial “yes”.

What about good old fashioned, baked into the cake, hard-wired desire for control? We know having a sense of autonomy increases the upfront yes to $ and the likelihood to stick around. We know this because we measure it directly from supporters. We also write our comms to be reinforcing of autonomy. This often means the “soft” ask and works better than the hard ask.

Does this explain why time is preferred? Is it seen as more autonomous?

And what about perceived impact? This is one way to make folks feel more competent about their giving (time or money) decision. If I feel more competent I’ll do it again.

In an experiment researchers showed participants a brochure about the nonprofit, Feeding America.

They divided participants into two groups and asked if they’d consider sharing their email to receive more information about volunteering (time condition) or donating (money condition).

The participants knew giving an email would result in some follow ask. Consider the oft-used newsletter signup that probably unwittingly results in a ton of asks to go along with the actual newsletter. Consider this an experiment in active lead-gen vs. passive.

Nothing to see here we didn’t already know, 15% gave email in time condition, only 8% in donation condition. Anybody who has ever done lead-gen vs. click to donate on Facebook has seen this. But why?

To say that it’s an “easier” ask of time is thin and off the mark.

In this experiment they also included survey measures because behavior data alone will never dig beneath the surface enough. They measured perceived impact, perceived control and warm glow and a few other possible explainers.

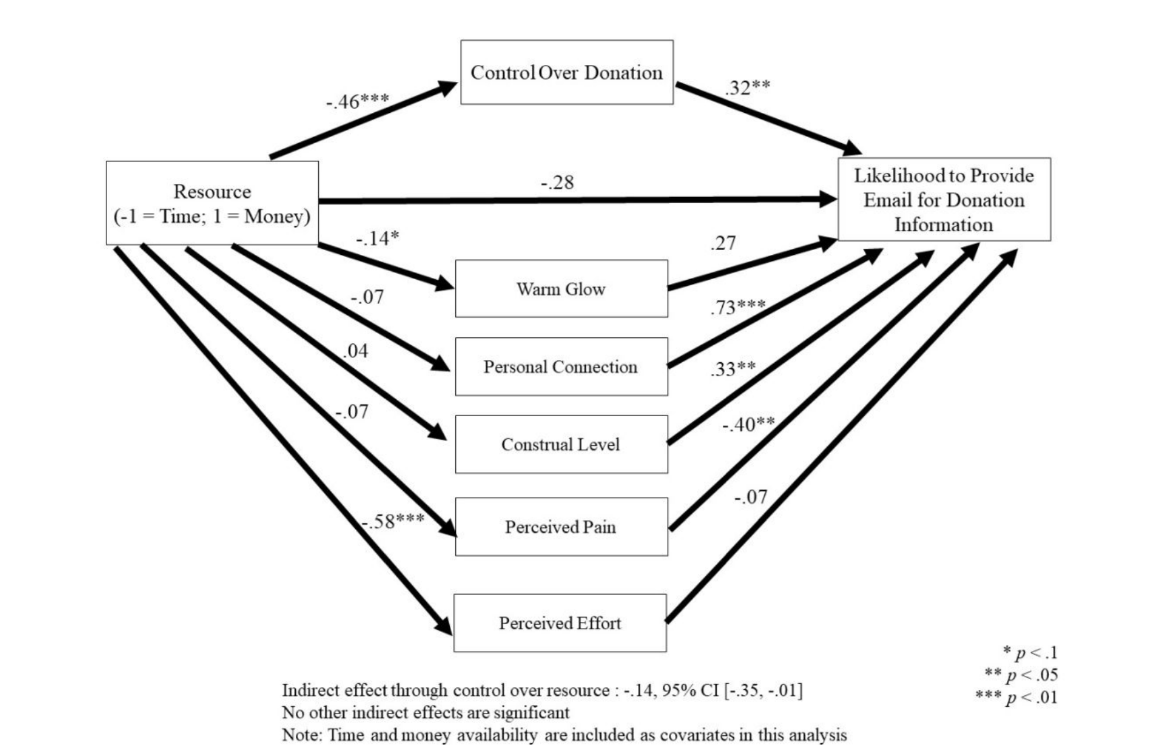

This model output is easier to read than first meets the eye. Follow the asterisks, if you see one on on the left and right hand side, it matters. If not, it doesn’t explain the preference of time over money.

Perceived control is the key ingredient.

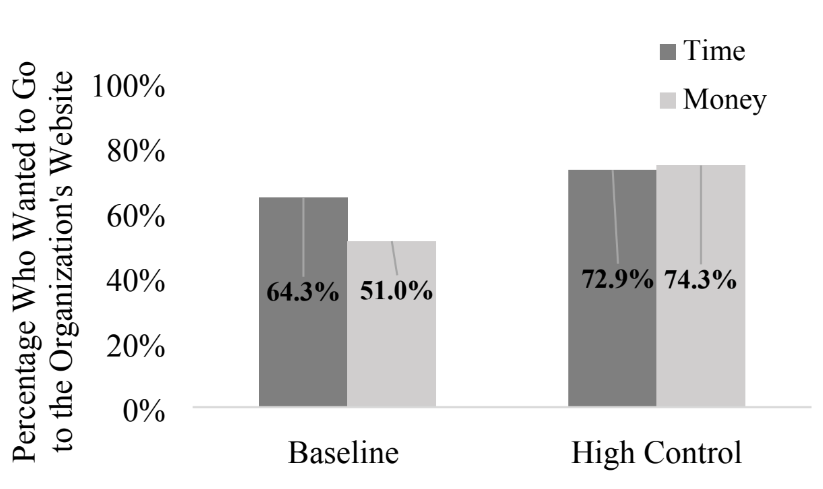

And here is what you’ve been waiting for. If we tell folks they will have some control over their time/money, we remove the seemingly baked-in advantage of time and its mental linkage to autonomy.

In the high control condition folks were told they’d have some choice over where time/money is allocated.

A few summary considerations,

- No, this doesn’t mean you have to do restricted giving.

- There are a lot of ways to convey control over where the money goes that keeps it unrestricted.

- We tested reply forms that asked about the program/issue they found most important and this can help convey autonomy.

- More importantly, stop with the ridiculous number of repeated asks in an email or letter. Talk about undermining control.

- Before you cite best practice for the 18 times you ask people to give in a fundraising letter, try this thought experiment.

- Imagine you are in a restaurant and the server asks if you want to tip at the end of the meal. It’s already customary (in US anyway) and no need to really ask. It’s slightly awkward but fine, you say, “yes, sure, we almost always tip and tip well, thanks”. But this server just read one of your fundraising letters before starting the shift and thinks it’s now best practice. This person then proceeds to ask you if you’d like to tip, eight more times throughout the meal.

Before you mentally shut down and say the metaphor has holes for X, Y and Z reason, just create your own mental experiment. It’s your kids maybe asking for something 10 times in 10 minutes or someone offering you a service at your door 10 times in 2 minutes.

We’ve tested this and I’m here to tell you what you’d know and assume to be true if the blinders of “best practice” weren’t there. Repeating the ask over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over…

is annoying. It also undermines control.

Kevin

P.S. Thanks to Mary Beth Healy, Chief Revenue Officer at Capital Area Food Bank and a DonorVoice Agency client for pointing me to this research.

After testing this, do you recommend a basic approach of fewer asks that fit organically and seem natural… or do you think a certain number of asks is usually ideal? (E.g., perhaps: one ask near the beginning, one in closing, and possibly one in the post script?)

Brett,

We’ve been counting the number of times a direct mail appeal asks for money. This is not a scientific sampling to be sure but it’s way higher than you’d expect is my guess. I’d put the Vegas over/under at 8 for starters.

It reads like chalk on a desperate chalkboard. This is learned and passed down as best practice. We’ve limited it to two asks and beat out the control with a bazillion. It’s so artificial and contrived if one can just take a step back and think about any other situation where a salesperson is pushy and repetitive. The “best practice” mail puts your worst, personal experience on steroids.

make it organic and natural. Don’t repeat everything ad nauseum. Pretend like you’ve never written a letter asking for money and see how it goes. Or better, think about what a letter would look like that didn’t ask, at all. How would you create a connection and instill an intrinsic sense of motivation to want to help in that letter? No asking as an exercise. Do you think the reply slip is lost of folks? It isn’t.

The letter has a job, get me to a mental yes to want to help. I can think of no worse way than repeating the drumbeat of “give now” to achieve that aim.

Thank you so much! This is very helpful, and has the benefit of being corroborated by intuition as well as data. 🙂

Eighteen times is certainly too many. Once is certainly too few (and that’s the mistake most small nonprofits make).

There’s a sweet spot in between, something like 3 times in a 2-page letter and 4-5 times in a 4-page letter.

Thanks, Dennis. That jibes with my experience. Always trying to navigate the path between experience and research, you know!

Just curious as to whether “factoid” is the right phrase to use back up your piece in the opening? “A factoid in support: Americans donate over $310 billion and volunteer 8.8 billion hours per year.”

Factoid: an item of unreliable information that is reported and repeated so often that it becomes accepted as fact.

Hi Paddy,

The Queen might quibble but factoid’s definition always included reference to a trivial piece of information along with the definition you cite. Per Webster’s “New World” Dictionary the word is “a single fact or statistic variously regarded as being trivial, useless, unsubstantiated, etc.” The Grammarist blog points out that that in the U.S., at least, “‘factoid’ is now almost exclusively used to mean ‘a brief interesting fact.Apr 25, 2016.