Donor Autonomy on Steroids

Is there such a thing as giving too much control to donors?

The sector generally operates as though donor control is bad at worst and undesirable at best This sector norm is reflected in many conventional practices: not publishing or promoting or making clear how donors names will be sold eight ways to Sunday for a (small) profit. Nor do we make it easy… or convenient… or prominent for donors to opt-out or set their preferences. Transparency is not the modus operandi.

Donor control is too often trumped by organizational habit, inertia or perhaps by the overt desire to try and maintain control by the organization itself. How many times have you heard the refrain about wanting unrestricted dollars or how restricted dollars are hard to manage?

It’s as if the downside of control is the only bit we see; the glass half empty. But what about the upside of control? We call it autonomy and the argument for it is theoretically strong. The human desire for control is one of three, key psychological needs. Giving control fosters high quality motivation. High quality motivation is the gift that keeps on giving, literally.

But we hear you Agitator/DonorVoice reader, “theory, smeary, what real proof do you have?”.

In-market testing has shown that simply telling people they are free to choose, increases compliance with the request. People give more if told “do not feel obliged…”.

Why is this? When a person’s perceived freedom to choose is threatened by a pushy fundraiser, or even a high-energy fundraiser, or a guilt inducing appeal it makes prospective donors resist the very thing we want them to do. In psychology this is called reactance. Make me feel pushed into a decision and I’ll resist like crazy, even if under other circumstance, I’d love to give.

Your style and approach that often restricts my sense of control is the very reason I won’t give. Preserving my autonomy and regaining control is more important than helping. The “do not feel obliged” language tackles this barrier head on.

But what about a more “extreme” version? What about telling a prospective donor they’ll probably say “no” as part of the ask? Insane. Why in the world would we even raise the prospect of saying no, much less risk the expected outcome? Social proof, another well “known” but poorly understood behavioral science principle, might argue this approach normalizes the ” no” behavior by implying we expect a no because that’s what most people do. Therefore, not only do I feel ok saying ‘no’, I feel downright good about it because it puts me in good company with all the other no people.

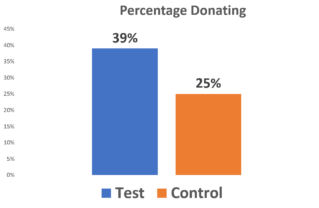

In a face- to- face canvassing test the control condition canvassers said “I wonder if you could help us by making a donation?”. In the test condition the canvasser said, “You’ll probably refuse, but I wonder if you could help us by making a donation?”. I own a canvassing and telefundraising company. We have extremely experienced, competent people running those operations who, importantly, manage these companies to purposefully be very different from the traditional agencies. Both businesses are built on behavioral science; it permeates training, scripting, compensation, culture…everything.

If I suggested the test summarized above, they’d laugh me out of the room. Hell, prior to coming across this study I’d throw myself out of the room. Not anymore. A 56% increase in the percentage of donors saying yes to the pitch that including the “you’ll probably refuse” preface. And no, the amount donated was not lower (it was statistically the same).

Why does this work? That answer matters and remains our biggest challenge as a sector; requiring ourselves to put more rigor in our testing. A hypothesis without an explanation of why we expect what we expect is called a random guess no matter how much we dress it up as the “h” word.

As Einstein said, if the facts don’t fit the theory, get new facts. It’s not theory, smeary. It is theory first and foremost.

There are three different explanations for the finding in this test:

- It creates a sense of control and autonomy. This is positive with the potential to deliver longer lasting effects – i.e. sticking with the monthly giving.

- It is psychological reactance. Tell me what to do, I’ll do the opposite. Make it a high pressure, guilting, repeat the ask 3 times (you know you do this all the time) situation and I am going to do the opposite. This taps into that but reverses course. Tell the person they’ll say “no” and our natural reactance kicks in and I do the opposite. This explanation doesn’t likely deliver any longer lasting positive effect (like a sense of autonomy) but probably also isn’t delivering lasting negative effects (“yes” now, “no” later).

- Impression management. The statement makes the prospective donor feel like the fundraiser has a negative impression of them. In the moment I want to manage my reputation to be positive and thus elect to give to prove the fundraiser wrong. I am a good person. This may be the win- the- battle, lose- the- war effect. More up front conversion, more back-end attrition.

If you run this exact test and it doesn’t work you can fall back on the explanations (i.e. the theory) to devise a new test. There is enough smoke around these seemingly small, subtle compliance techniques to believe there is fire.

Just know what you are testing and why. And while we’re at it, let’s focus on the glass that is likely damn near full if we have the courage (borne of knowledge) to make it so with “extreme” donor autonomy and control.

Kevin

Thinking back to the 80s when I was trying to get monthly check paying donors to convert to automated payments. Donor’s control was a very big issue. An important aspect of our pitch was “you can stop these at any time”

Gayle,

Thanks for the comment. That line or sentiment is (or should be) an important part of the pitch in 2021 too, even though most folks are signing up directly to digital payment methods these days.

Could another possible explanation be that it starts the conversation with low-pressure? The out for the perspective donor is available right at the start, no is expected, so they might be more willing to engage in the conversation and be moved by the pitch. I shut down a conversation before it starts with any door-to-door salesperson, telemarketer, canvasser so that I don’t have to come up with a reason to say no later (“no sorry, I don’t care enough about puppies to donate” <- who wants to be that person?).