How to Have More Winning Tests?

Stop designing tests assuming everyone’s the same. 99.9% of tests are of this variety, the random nth, A/B test.

Hidden in many “losing” test results is a test idea that worked for some people and not others.

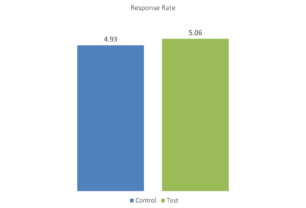

Here are results of an experiment with donations going to World Vision and prospective donors randomly split into the control (altruism) and test (self-interest).

Nothing to see here. The test lost. Discard, move on, declare failure. That is the best choice if the alternative is to break out the test response rates by random groupings within the test group. If you append lots of 3rd party data or just look at random RFM groupings or demographics or channel behavior you’ll see lots of sub-groups within the test group that beat the control.

There is a 99.9% this is random noise, but it may feel like signal. In fact the human brain is trained to see patterns and explanation, even where none exist.

Consequently, the human bias is to find something that’s actually nothing. But our bias leads us to come up with a reason why it’s something – e.g. “people in our low dollar, high recency RFM bucket loved the test”, or ” people that collect stamps and skew to Generation Whatever hated our test.” But, if your test wasn’t designed for these groups beforehand, finding these random differences after the fact is a waste of time and money.

What about designing your test assuming people will respond differently based on who they are as people? The World Vision test was such a test. The first bar chart is what we expected, no difference if you mash everybody together.

The altruism appeal – dubbed the control because it’s more typical in the sector – had the ask framed as, “Any donation you make will improve the happiness and wellbeing of an African family.” The researchers didn’t think this would work well for everyone, they thought it would work for people high in Agreeableness as an innate, personality trait.

The self-interest appeal had the ask framed as, “Research by psychologists shows that donating money to charity increases the happiness and wellbeing of the giver.” Again, this wasn’t a test idea developed to work for everyone, only those low in Agreeableness and higher in the innate Neuroticism personality trait.

Why Personality? It travels well. It’s part of you. It is measurable, targetable, we know how to message to traits and most importantly, our personality determines much of what we pay attention to, what we consider, and what we act on.

Framing appeals to match who I am versus who I am not seems obvious except obvious is in short supply so it ain’t really that obvious.

The experiment included measuring Personality traits after the donation in order to break out donation behavior by trait and by control/test. What did they find when the analyzed the results the intended way – i.e. not lumping together the two trait types and blurring any differences in behavior?

The test won among those low in Agreeableness and higher in Neuroticism and lost for those high in Agreeableness.

Framing matters. But it matters differently for different people. You do have different donor segments but their ‘why’ of giving has zero to do with demographics, behavior, channel or any other internally defined segmentation. It also has zero to do with random, persona clusters that were created by throwing everything into a statistical blender.

Start with why people do what they do, recognize it isn’t the same answer for everyone while knowing groups of similar people exist. Build a test aimed for a specific group but also include a group you don’t think it will work with to more fully establish cause and effect.

The random nth should die a quick death. It won’t. But it should…

Kevin