Survey Question Design 101- Part 2 of 3 on Donor Surveys

A caveat upfront: Our view is that survey research, especially questionnaire design and analysis is not art but science.

This means it is not a subjective interpretation of what is and is not good design and analysis. There are rules from the social sciences and the statistical sciences. Violations are sometimes subtle, sometimes egregious. The garbage in, garbage out adage is apt. That said, it can still be non-garbage in and still garbage out if the design and sampling are OK but the analysis stinks.

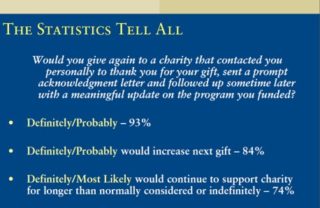

This example serves as a poster child of what not to do on a variety of fronts. (it should also be noted, this question was “designed” by a person who is held out as a “survey expert”; thus, caveat emptor seems apt here.)

The issues with the question structure:

- It is a leading question that is biasing people towards a “yes” answer. The question may as well read, “If we do a whole bunch of nice stuff (or stuff that we think is nice) and make you feel good, and your money wasn’t wasted, will you give again?”

- It is triple barreled in that it is asking about three discrete actions and bundling them all together. What if the person trying to answer this assigns value to the update but not the personal contact? How do they answer this? If these are activities that take charity time and money and may or may not be valued by the supporter then we really need to identify separate, discrete measures for each to understand their relative impact on giving. In other words, the question should be 3 different items, not one.

- It asks about future intentions. Questions asking us to predict our future behavior are notoriously unreliable especially when they are conditional on X, Y or Z happening. To correct for this and for #2, it requires knowing whether these are activities that already occur – chances are good that they are. In which case, make these separate questions (pt. 2 above) and ask for a performance rating on how well the touchpoint/interaction does its “job” – not whether they recall receiving it but did it do the intended job – e.g. show them how their money was spent, make you feel appreciated. And leave an option for “unable to rate” if they don’t recall the interaction. Analysis can then be done using actual giving (if this was a donor sampled from the house file) to determine, statistically and in a derived fashion, whether any of the 3 actions impact giving and if so, to what extent. [Foreshadowing: we’ll hit on this in more detail in the next post…does this even qualify as foreshadowing?]

If, on the other hand, these are prospective activities and we are trying to determine if doing them will matter to future behavior then we need an entirely different methodology to evaluate these and simple survey questions won’t cut it. It requires analysis of the sort that goes beyond the purview of this post but you can read more about one option that can be used, here.

We also need to take the reporting of the (meaningless) results to task. If “Definitely” and “Probably” are in fact, different expressions of likelihood on giving then it makes absolutely no sense to report them as a collapsed category. If “Definitely” is 1% and “Probably” is 92% we probably (or is it definitely?) have a different take on these findings. It is well documented that the end-points on survey questions tend to represent well-formed opinion, solid judgments (how those end-points are labeled matters a lot however).

Conversely, the mid-points are the mushy middle with very little separating “Probably Would” and “probably Would Not”, for example.

Here is a non-exhaustive list of “Do’s and Don’ts” for questionnaire development.

- Ask questions that are clear and specific. Ambiguity is the devil and there are many, many details.

One study found that there were four distinct interpretations about the term “big government”. For attitude measurement you’ll need consider the object being measured. This can be something specific like President Reagan or cornflakes. It can be also be about more abstract concepts like civil liberties or climate change. The more abstract the more likely it is that you’ll want to unpack the concept to get more specific.

- Closed-ended questions should include all reasonable response options.

The list of options should be exhaustive and the response options should be mutually exclusive, meaning they should not overlap.

- In general (there are exceptions), make the scale bipolar, not unipolar.

Was the donor service representative friendly? (yes/no) is not as useful as “was the donor service representative friendly or unfriendly?”. In the unipolar instance we must assume too much about the “no” answer. Does that mean that they found the person unfriendly? Not necessarily, maybe they didn’t form a judgement on that dimension of the interaction. Maybe they care about ‘friendly’, maybe the don’t.

- It’s often better to include degree of sentiment within the bi-polar scale and what tends to work best is 5 to 7 scale points that are fully labeled. For the donor rep example this might be 1 to 5 scale with 1 being very unfriendly and 5 being very friendly with 2-4 labelled appropriately in-between. Generally providing a middle category is best. There is wide debate on this and no clear consensus in the field. And, it can/will differ so consider this as very general guideline.

- Simple language, no jargon. No acronyms. No flowery, value laden language.

- Offer a choice between alternative statements as part of the survey. There is a tendency (not evenly distributed in population) for acquiescence bias to be agreeable to statements offered. You can account for this with some positive and negative framing (to be reverse scored in analysis) of a given concept but can also account for it with alternative statements and forcing a choice on which one better matches their view.

- Avoid hypotheticals

- Know for certain how each question will be used in the analysis. If it isn’t clear, cut it.

- Order questions from more general to more specific

- Rotate items within a battery of items intended to measure some underlying concept.

I welcome your questions, comments and any examples –good or bad– you wish to share.

Kevin

P.S. Next up: Part 3-What is Important to Your Donors? How Do You know?