The Investment Paradox – Barriers To Growth, Part 2

There’s no question that the shortage of investment funds for fundraising is perceived as a principal barrier to growth.

That sentiment was voiced by many attending the DMANF Leadership Summit last week, and it’s certainly a reason offered in a lot of the comments and email from Agitator readers.

The solution to this problem may lie within your organization itself.

Most charities have significant reserves. Which is no bad thing in and of itself. But, many charities have larger reserves than they need, which is always a bad thing as donors never give our causes money so that we can stockpile it in reserve.

Most charities invest their surplus reserves in stocks and bonds, employing fund managers who, for a fat fee, will manage their portfolio in the hope of generating a better than 1% annual return, which is what certificates of deposit are paying in the U.S. and 1.6% in the U.K.

Trustees love the duty of managing reserves. But, they’re doing a lousy job. Over the last decade or more, returns from such investment have been poor at best, flat or even negative for long periods.

Yet investment in fundraising is another story entirely. It’s almost a dereliction of a board’s fiduciary responsibility to not invest some of those reserves judiciously in donor recruitment and development. An investment that would yield an annual rate of return for most organizations of 20%, 30% or even more.

This Investment Paradox — investing in stocks and bonds while ignoring the far higher yield of investing in your own fundraising and growth — is probably little known or noticed by most boards and CEOs.

It’s time they wake up!

And sounding the alarm is exactly what British fundraising strategist Giles Pegram set out to do two years ago through an analysis of the investment returns of 32 U.K. charities.

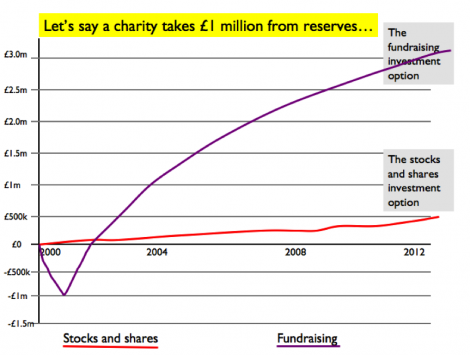

He assumed a scenario where, instead of investing in the usual stocks and bonds, the charities would take £1 million from reserves and invest in their own fundraising programs.

As you can see from the chart below the average return on the fundraising investment for these charities was vastly more impressive than the return on conventional investments.

I’ll take a 3 to 1 return on investment over a 0.5 to 1 return on investment any day. I bet your board and CEO would too. (Once they get over their embarrassment.)

And I know for certain your donors will be a lot happier knowing you’re using some of their money by investing wisely — and with quite high returns — in building the future of your organization.

Oh yes, I can already hear the naysayers in the C suites and boardrooms. “But, it’s risky and unconventional.”

Nonsense. Because you’ve already tested and know near-certain results of stable, proven fundraising programs — acquisition, monthly giving, whatever — you know precisely when the funds can be paid back and how much you’ll make on the investment. Can’t say that about many banks these days.

So why not do a comparison for the CEO and Board. Show them what the current return is on the invested reserve or endowment funds. Then show them what the return is on your fundraising.

If you don’t get a raise, you should definitely update your resume because you’re dealing with folks who either don’t understand the value of money or don’t care.

Giles, you get an Agitator Raise for shining the spotlight on the Investment Paradox.

Is your organization putting its reserve funds to work in growing its future?

Roger

P.S. In case you’re not sure how to go about calculating the comparisons between what the board investment committee is getting and what your fundraising program returns, we’ve prepared an AGITATOR GUIDE TO CALCULATING INVESTMENTS.

This is exactly the conversation we had with the marketing team back at budget time.

dk

Hoh boy, right on Roger!

There’s a new fundraising term that staff should introduce to their board. The word is “profit.”

I think if we talked more about profit we just might get their attention and get them to understand that we are a money-maker, not just a cost center.

Love your point about wise use of reserves.

Gail Perry