The Taxman Cometh, Part 2: Maybe the 2017 Tax Bill Won’t Kill Us All

Since I ended my piece yesterday the doom and gloom note of the existential threat to all philanthropy, this is an odd, or at least paradoxical, piece to write. But there’s some counterbalancing evidence that we may not be peering into the abyss created by the new tax cut law.

Hope #1 is that donors will wend their way around the changes to the tax laws. As water seeks cracks, so money seeks loopholes. One such loophole (definition: something someone else uses to avoid taxes) involves the use of donor-advised funds. The day after the tax bill passed, the New York Times reported on using this strategy combined with so-called bunching of donations:

“Someone could ‘bunch’ several years of donations to a donor-advised fund into one year, and take the tax deduction, but then have the fund pay out the gift annually in equal amounts. The charity would get the same amount each year, even in years when the donor did not itemize deductions.”

In fact, by donating appreciated stock to a donor-advised fund, you can double your tax savings.

There are some issues with this. Leaving aside the concerns of philanthropy being only a rich person’s sport discussed yesterday, there’s actually no requirement for these funds to paid to charity on any timetable. Thus, dollars intended to clothe, feed, save, cure, fight, and succor could instead be parked in a mutual fund indefinitely, as $85 billion currently is.

But, for the donors using these funds as intended, it is a way to get more bang for your charitable buck.

Hope #2 is that we aren’t hearing comments from donors about the tax law change. Of 3000 comments to a major US nonprofit at the end of 2017 through DonorVoice feedback solutions, six people talked about the changes. Four said they wanted their gifts to count for 2017 because of the tax changes; one said they’ll continue donating despite the changes; and one said the amount was probably because of the tax changes (but didn’t say whether that was up or down). Hardly a mass exodus.

This was unprompted feedback; what about feedback specific to the tax law from donors? Here we are indebted to M+R for running a public opinion survey on this. Their details are here and well worth a read. A few highlights:

- Overarchingly, I’d agree with the proviso they put forth at the beginning of their analysis:

“And, it’s important to note here that what people say is often not what they do. So, while we’re paying attention to what we learned in our research, we can all agree that the best information about the impact of the tax law will come when we look back on our 2018 fundraising results next year.”

So get our your grains of salt.

- For 2017, most donors said the tax bill didn’t change their giving (53%). Twenty-seven percent said it had increased; nine percent said it decreased.

- For 2018, most donors said it won’t change their giving (51%). Thirty percent said it will increase their giving; nine percent said it would decrease.

So donors aren’t saying their giving will change much in 2018 compared to 2017. As Yogi Berra put it, it’s difficult to make predictions, especially about the future. But, in our case it’s better to see these results than more negative prognostications.

Hope #3 is that we aren’t seeing evidence of decreased giving so far. To continue with M+R’s data, they looked at organizations that hadn’t been impacted by Trump or disasters (some would argue I could say disasters and leave it at that). Of the seven, six had January 2018 results that surpassed their January 2017 results. So that, also, is good news.

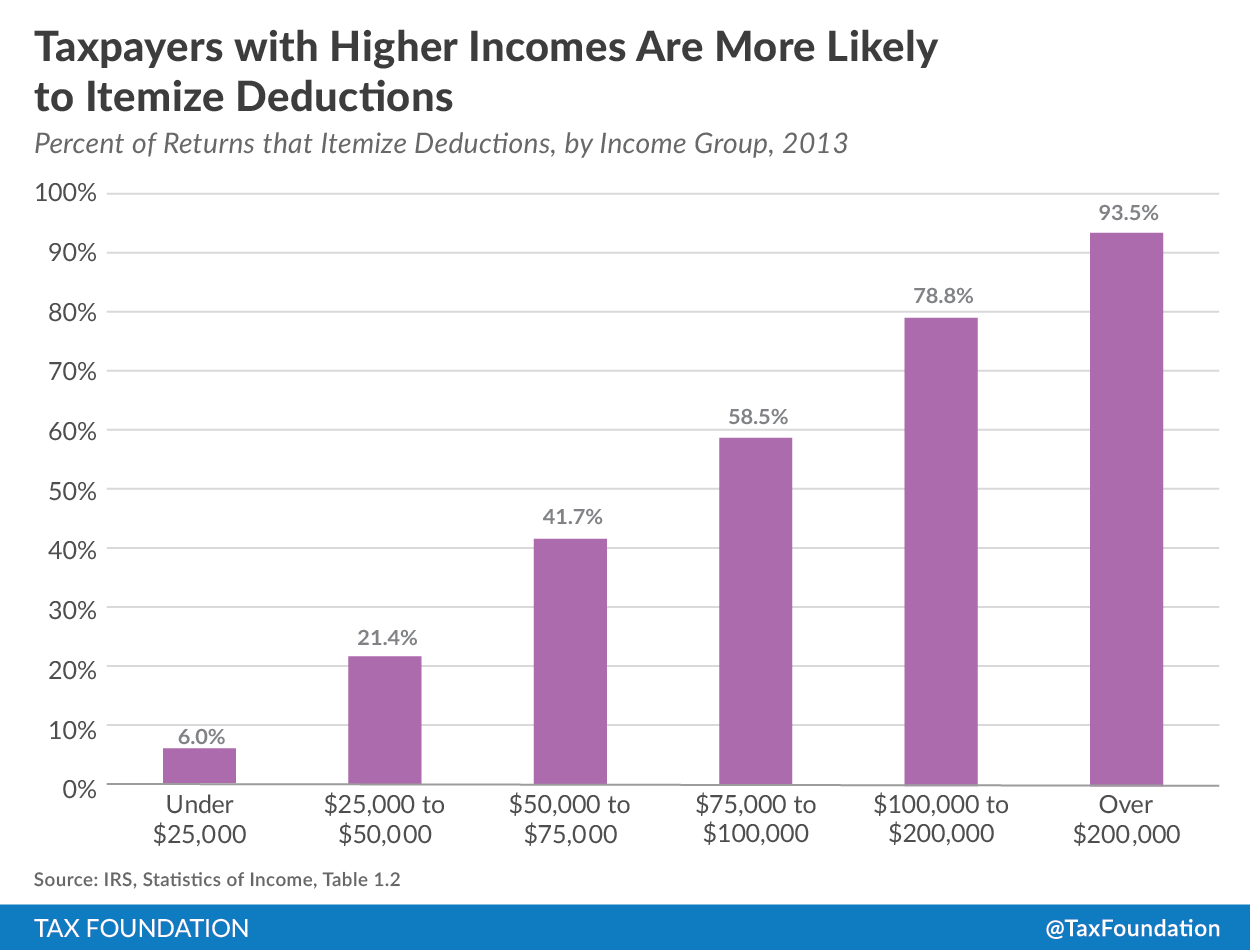

And Hope #4 is that the people who are most impacted by these changes also got a tax cut. The change in itemization will largely impact donors in the $50,000 to $400,000 annual income range; as you can see at right, from the Tax Foundation, they are the people currently itemizing who likely won’t do so anymore.

And Hope #4 is that the people who are most impacted by these changes also got a tax cut. The change in itemization will largely impact donors in the $50,000 to $400,000 annual income range; as you can see at right, from the Tax Foundation, they are the people currently itemizing who likely won’t do so anymore.

While this may cool their charitable ardor, they may have more take-home pay with which to give. The tax rates for $165K to $315K in income went from 28-33% to 24%. Assuming no alternative minimum tax, these donors will have $7-15K more in income this year than last. Presumably, this is “found” money than could be used to increase charitable giving (or not ).

There are donors from states with high state tax rates, which are no longer deductible, to whom this won’t apply, but it could be an impact for many in the $100K-$400K bracket who are most impacted by the changes in itemization.

In the balance of these two positions, I’m persuaded to take a wait-and-see approach to the amount that will be given to nonprofits. I feel like it may be more of a downslope than a cliff, as increases in revenue help buoy things early on, but fade in the long-term, and perceptions of tax-deductibility change over time.

I’m also concerned about where philanthropy will come from going forward, given there’s every incentive for us to use the Willie Sutton rule and go after major donors, because that’s where the money is.

But beyond this, what do we do because of these changes? That topic, tomorrow.

Nick

In the worst case scenario, presented by so-called experts, philanthropy will decline by $21 billion. When applied to 2016 giving and GDP, philanthropy as a percentage of GDP would still have been around two percent, the historical figure. So, while $21 billion is a lot of money, relative to overall giving it is a small fraction. In other words, the nonprofit sector need not be horrified by the prospect of the worst case scenario being realized.

Now, having said that, I also don’t believe we need to worry too much about the worst case scenario for another reason: It’s unlikely.

If the new tax code results in economic growth, we can expect to see an increase in philanthropy. The folks who calculated the worst-case scenario did not take economic growth into account. Historically, overall philanthropy has been approximately two percent of GDP. This correlation will likely continue.

There are other reasons to be optimistic. For example, the limitation for the deductibility of contributions to charities increases from 50 percent to 60 percent of adjusted gross income. The Pease Amendment, which phased out the charitable giving deduction for wealthy tax filers, has been eliminated. These changes make charitable giving less costly for wealthy donors.

Another reason I’m not worried is that many tax benefits were left untouched. For example, donors can still avoid capital gains tax by donating appreciated property. Donors can also give through Donor Advised Funds and from IRAs.

For some donors, the change in the tax code will result in increased benefit for giving now that state taxes can only be deducted up to $10,000. It’s a bit complicated to explain briefly here, so I’ll refer people to Dr. Russell James’ article that explains this more fully: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/how-2018-tax-law-increases-charitable-giving-russell/

For a more detailed explanation of my optimism, folks can read my post on the subject: https://michaelrosensays.wordpress.com/2018/01/05/how-bad-is-the-new-tax-code-for-your-charity/

As with yesterday, I agree with almost everything you said, with one quibble.

$21 billion would be a fraction, yes, but a significant one. While we’d remain in that 2% of GDP range, individual giving was $390 billion, so this would be a drop of about five percent. If individual giving did drop by 5%, many Agitator readers would lose jobs or be under significant pressure because of failure to deliver budgets, not to mention the cuts organizations would have to make to mission. For perspective, individual giving went down 8% in 2008 in the Great Recession. So, more than half of the Great Recession = significant in my mind. That said, I agree it probably won’t be that bad, but I wouldn’t want to diminish it if it is.

As for economic growth, I’ll spare folks the ideological arguments on this topic. Rather, using the assumptions from the tax bill, the goal is 3% GDP growth and there’s a question of whether that could be reached. Real GDP growth was 2.3% last year. So would an additional .7% in GDP growth (even if achieved) stir an impact? As you say, people usually give about 2% on average of GDP. So 2% of .7% is .014% growth that would be unexpected from a better than average economy. If there is a danger from the factors from yesterday, it would swamp this impact.

It’s my hope that this will all be irrelevant in a year – that people will keep giving because of their altruistic motives and that nonprofits are able to make a shift away from using deductibility as a reason to give.

But like the old Reagan ad said, “Since no one can really be sure who’s right, isn’t it smart to be as strong as the bear? If there is a bear.”

Thanks for your comments on these – they’ve made me smarter!