The Weak-Minded Nonsense of Generational Marketing

One of our most enjoyable and simultaneously painful Don Quixote quests is attacking the windmills of horseshit that are generational marketing and other random segmentation schemes posing as human insight.

We’ve cited reams of evidence and data galore undermining the weak-minded nonsense of generational marketing, the clusterf#$% of cluster analysis and personas to nowhere. (Here, here and here for starters.)

We’re reminded of all this by a BBH Labs study that provides yet another gem of proof highlighting how profoundly silly this all is.

These generational cohorts (Millennials, Gen Z, Gen X, Boomers) are random collections of people who share nothing in common (beyond what random chance would dictate) save for being born within two decades of each other.

For example, in the UK there are 78,000 millennials whose children are also millennials. And yet, we speak of parent and child as if they were one in the same. But if that same child were born a year later, they’d fall into Gen Z and be seen as utterly distinct.

The reality is there are many instances in which parent and child may be alike for our purposes – e.g. both identify as nature lovers and are open to supporting a nature charity or both high in agreeableness Personality traits and should be messaged to accordingly.

Butt those important similarities and differences will never be found in the horoscope equivalent of generational marketing nor in random, statistical clustering solutions that throw everything random and non-random into a pot and stir.

BBH labs proves this folly by using publicly available survey data courtesy of TGI that runs a monthly, omnibus survey. BBH created the “Group Cohesion Score” to calculate the like-mindedness of groups of people based on attitudes and lifestyles measured in the TGI, year-long, 2019 dataset. The survey items ranged from mundane (“I use a refillable water bottle most days”) to the metaphysical (“there’s little I can do to change my life”).

The baseline Cohesion Score is 48.7% for the UK population, meaning on whole, all of the UK agrees slightly less than half the time.

The wide range of statements will not produce unanimity of thought among any preselected group but, as an example, Mormons are more homogenous than left-handed people and thus have a higher Cohesion Score, which lends some validation to the concept. Though we’re sure BBH would be the first to admit the only purpose of the score was to affirm their view that generational marketing is garbage.

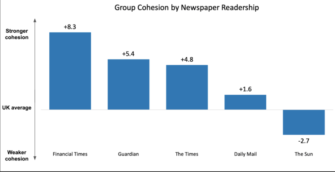

That said, and as further validation of the score having merit, here are Cohesion Scores for different newspaper readerships.

The Financial Times, a highly niche publication, has a higher reader Cohesion Score than the tabloid, The Sun, whose negative score means you’ll get more agreement among a randomly selected group of Brits than a group of regular Sun readers.

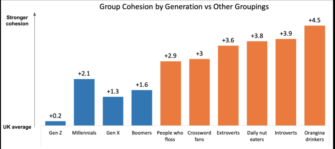

And how do the generational cohorts do? Much worse than daily nut eaters which is a ridiculous group unless you are a nut manufacturer but that makes it one better than marketing by generations since they have virtually nothing in common being barely better than a random group of UK citizens.

If we’ve said it once we’ve said it a thousand times, there is far, far more difference within these random, 16-year birth cohorts than between them. If your segment has more variation within it than with the surrounding segments, it is not a segmentation that should ever see the light of day. Similarly, if you grouped people based on random attributes (like birth year or a smattering of attitude statements or a smorgasbord of whatever you can find), it isn’t worth the PowerPoint slides compiled by the agency sharing the “results”.

And yet, seemingly countless charities are relying on or at least spending money on segmentations that suffer from these failings; random groupings that seem alluring and yet have more variation within than between and/or are grouped on things that don’t matter to the giving decision.

Why? BBH Labs shares their point of view on fellow marketers:

“Why do we fall prey to these sweeping, often useless groupings? Part of it is laziness. Carrying around a caricature is easy, negotiating the complexities of real, breathing human beings is harder. We reduce people to tropes (millennials = experiences, avocados, purpose) to avoid the real work of understanding them. And whilst these shortcuts can be hidden in pretty decks, there’s no disguising them in the work.”

(The “disguising them in the work” phrase contained a hyperlink in the original that we’ve shared in the postscript It is an actual 30 second spot for Diet Coke– not a spoof.)

People are different, just not in the ways often relied on – e.g. demographics, random attitude statements, behaviors (e.g. our active/lapsed/one-time/monthly/RFM segments).

What unites us and makes us different is Identity, Personality and our perception of experiences. Measuring these is what matters. Grouping by these characteristics is what matters if effective fundraising is your aim – fundraising that doesn’t rely on gross stereotypes or tropes like “ask-thank-report back”.

And yet, like Don Quixote, we’re likely being met with the mental equivalent of getting knocked off our horse attacking these generational and other nonsensical persona type windmills. Confirmation bias is powerful and rears its head when one is met with evidence that runs counter to existing beliefs. It causes people to dig in deeper and be even more committed to their worldview, no matter how wrong it is.

So, screw it. Have a Diet Coke and watch the ad, brought to you by an agency whose brief said Millennials like to express their values through their purchases, are independent, like leisure/athletic wear, have or would stay in a yurt and run marathons.

Kevin and Roger

P.S.

Interesting article, thank-you. I wonder about the application of these results. In my experience, generational segmentation is often more about choosing a channel and donor capacity than about messaging. Our major donor audience is older. We don’t solicit them on Tik-Tok. When we send to our young alum, we don’t ask for $10,000. We sometimes use more nostalgic messaging for older alumni and those campaigns have been successful, but we recently had a giving day campaign which included a (very different)nostalgia message for new graduates and it was also successful. Payment methods also seem to vary greatly by audience. Many 70-somethings like to send a check. We can observe that doctors and professional athletes are less generous and the business school graduates give more to their college, but we still haven’t found a way to message to take advantage of that knowledge.

Paul (or is it Great Scot?),

Thanks for commenting. What you’re describing is using age as proxy in a tactical way to increase efficiency, which can make sense. Of course age as proxy (or other data as proxy) has errors of omission and commission. For example, there are 20 and 30 somethings (recent grads) capable of stroking large checks and of course older alum with limited means. The more direct measure is wealth and income data to reduce those omission and commission errors. Any group that does anything can be described demographically. And if you have two groups and profile their demos, they will be different – a little or a lot depending on how the groups were created/identfied/segmented in the first place. But, descriptive demos aren’t the same as causal factors. As you noted, the nostalgic theme did well with older and younger folks, suggesting the reason it did well had nothing to do with age but I’m sure you could profile the nostalgia responders and non-responders with demos and find differences and the more data you profile with, the more differences. 99% of those differences are noise, not signal.

The profession findings could be causal (at least in part) or just noise. My professional Identity isn’t necessarily tied to my undergrad experience but set that aside. Unless you are marketing to doctors and drawing an explicit connection between that profession and their college experience and the ask (e.g. help provide scholarships to pre-med students) then why would you expect them to give more? because they have more? Take any results (giving) and break them out by profession and you will find professions at the average, above average and below. Noise or useful insight? That is the million dollar question.

LOVE this!

thanks Harvey, glad you like (love) it.