Who Owns the Story?

That’s the rhetorical question underlying an Amref Health UK report, a charity focused on health in Africa. The report shares loads of useful detail on a direct mail test pitting what they call participant stories against charity stories.

The report is authored by outside consultants, Jess Crombie and David Girling, in partnership with Amref. The test was done to shed light on what the authors consider a moral and ethical problem of charity fundraising reinforcing a donor as savior vs. helpless beneficiary dynamic.

The authors argue for what they dub participant-created solicitations as a way to overcome this moral problem. We’ll leave the moral debate to others as our interest is in stories well-told. So, we were curious about the curation and development process for the participant/beneficiary mailing, which was done almost entirely by those in the local community including photos, layout and copy writing with limited support and guidance.

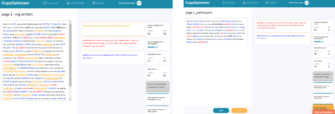

This mailing was done as a test against the standard appeal written by the charity. The package format was the same, and while the reply slip wasn’t shared, I’ll assume it too was identical. That leaves words and pictures that were different. As illustration, here’s the first “page”.

Pretty big difference without reading a word. The participant-created pack uses lots of images, far fewer words, no organization branding, salutation, etc. The middle section and last page comparisons show similar contrasts.

The financial results are murky but the value of this work is not in the head to head results. I’ll say it again, the value is not in the head to head.

Ok, having said that twice, I’ll explain why.

Beware of Bias and Wishful Thinking in Evaluating a Test

The authors argue the participant pack “won”. I’d politely call that wishful thinking that can contort, twist and undermine the value of the work by exposing a bias to torture the data to fit their desired outcome. “Losing” tests have plenty of value if based on a theory driven rationale from the outset.

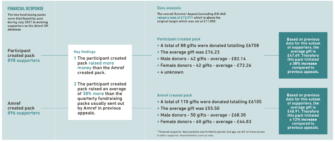

Here is how the authors chose to describe the financial outcome. They declare victory on the basis of total dollars raised and a higher average gift. What’s not calculated or shown is the response rate is statistically (with 90% confidence) lower for the participant pack: 9% vs. 12%.

Some might argue total revenue is the way to judge this test and therefore, the participant pack did indeed win. In response I’d say nothing was done in the test to overtly influence the average gift, making this metric all noise, no signal. Averages hide a lot, and I suspect if you strip away outliers and look at median gift all the difference goes away.

The aim of the pack, in part, was to be more authentic and increase “engagement”. But, lower “engagement” vis-a-vis statistically lower response rate being spun into unequivocal victory is a bridge too far.

Especially since the conclusion in the report is that participant-led packs can work as well or better than organization- created ones based on this single, financial outcome.

Curating stories in a way that makes the beneficiary/participant feel a greater sense of control and mastery is a good outcome for them. This process seems to have accomplished that as the report details feedback from those participants. Success.

Turning those ‘raw’ ingredients into a story well told that also increases the donor’s sense of autonomy and relatedness and competence is a very useful fundraising goal. Was the story well told in either pack? The report subjectively reviews each and gives a strong nod to the participant pack.

But, an objective analysis using our Copy Optimizer tool gives only a slight nod to the Participant copy (right panel) with a higher Overall Engagement Score (63 vs. 59) on the back of a stronger Story score (76 vs. 67).

These objectives scores tell us the copy isn’t what won the day for the organization-created pack nor that the participant-created pack sets itself apart on these scores.

Perhaps the better answer is a third way, a hybrid approach that morphs the two.

Having an editor rework copy would not be an automatic undermining of the ‘authenticity,’ nor autonomy, nor a nod to saviorism. The best professional writers on the planet all have editors.

Editing can improve the sense of participant competence and relatedness (two key psychological needs) if done collaboratively. This, in turn, would fuel internal motivation for those participants.

Most people are lousy at writing, it’s hard and it takes work. You don’t get bonus points because its raw, unedited and “authentic”.

Weak writing is weak writing and who the writer is–whether participant/beneficiary or the organization copywriter doesn’t change that.

The authors also note how the participant pack didn’t address the donor directly nor have a bazillion asks for money, as is the traditional approach.

Again, perhaps a hybrid route is best. Involving the reader is done with story but also with making it feel like a personal conversation. That invariably involves pulling the reader in with, for example, 1st and 2nd person pronouns and talking to that person.

This needn’t be done in a way that invokes saviorism (not sure who makes this judgement?) or making the donor the artificial hero (a silly aim and trope), it’s a conversational feel pulled off in an otherwise one-way communication.

Again, a cool report whose real real value is the detailed process to locally curate the stories. So I would encourage reading their report here.

Going from curated story to fundraising that works is a work in progress and it isn’t helped by spinning a tale of unqualified success.

Kevin

The other problem with this test is the big conclusion drawn from the results. If we grant that the “participant” pack is the “winner,” we still haven’t learned that the category of participant-created fundraising is more effective than traditional fundraiser-created fundraising. We’ve only learned that this particular pack with its specific content did better. Useful to know, but we haven’t yet discovered an entire new much-better way to raise funds.

To conclude a sweeping principle about fundraising, you’d want to see a number of different tests that probe this idea in different ways and in different contexts.

It’s great to test new ideas and approaches. That’s how we stay good. But turning specific learnings into broad principles is going to lead you into real trouble.