Activism’s Double-Edged Sword

Social activism and creating a “movement” is hard work, made harder by a conflicting reality. More extreme actions, often effective at gaining (media) attention and increasing pressure on organizations or institutions, are likely to reduce popular support.

What constitutes ‘extreme’? Is it in the eye of the beholder or context dependent? Blocking highways may be considered extreme in one instance but not another.

Having said that, recent experiments taking advantage of current events – e.g. anti-Trump rallies and Black Lives Matter (BLM) – should give pause to the view that all “press is good press”. In six experiments across a host of scenarios the overwhelming evidence is:

-

- Most people have a shared view of “extreme” that doesn’t differ along racial and political lines and even pre-existing attitudes (for/against an issue)

- This shared view results in extreme protest (e.g. threats of violence, actual violence or vandalism) reducing support for the movement and the broader cause.

And like all good research, it unearths a “why”; namely extreme protest is seen as immoral. This immoral judgement reduces the ability of people across race, political and belief spectrums to socially identify with the protesters.

Here’s two of these experiments and our advice.

Experiment One – BLM.

Study participants read one of two BLM news articles;

- Extreme: An article in its published form describing a BLM protest with chants encouraging violence against police (e.g., fry ‘em like bacon).

- Moderate: A slightly modified version of the same article that instead described the chants as anti-racist slogans (e.g., Black Lives Matter chant)

Participant race and political ideology was measured in a survey prior to reading the article. After reading the article participants answered additional survey questions measuring,

- How extreme they find the behavior

- How much they socially identify with the activists

- How similar they feel to the activists

- How willing they are to join the movement

- How much they support the activists

- How much they support the cause of the activists

The moderate condition was seen as less extreme so the manipulation was successful. Further, those in the extreme condition were less likely to identify with or support the activists. This finding did not differ by race or ideology even though, as expected, blacks and liberals were more likely pre and post experiment to identify with and support the movement, their support went down like every other racial and ideological group. Said differently, “extreme” protest actions lead to less popular support for a movement, including those most aligned with it.

Interestingly, of the six experiments all using different conservative and liberal, real-world examples, the BLM experiment is the only one where the extreme condition didn’t lessen support for the broader cause of eradicating racial discrimination. This is likely because, compared to other issues, there is almost universal support for the cause and it’s strongly held by most.

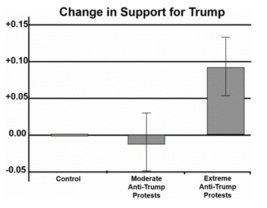

Experiment Two: Anti-Trump Rally Experiment

In this experiment researchers measured race and other demographics, political ideology and support for Trump prior to the experiment. Participants then watched one of three videos,

Control: A video of men building a deck

Moderate Condition: A real video news report of a protest outside a Trump campaign event showing protesters holding up signs and chanting, but not acting in a confrontational manner and the reporter describing the protests as “heated but civil”.

Extreme Condition: A real video news story where anti-Trump protesters gathered in a busy street, physically blocking carloads of Trump supporters and described by the reporter as creating a “potentially dangerous situation”.

Participants answered the same questions after the video about identifying with the protesters and support for the cause and for Trump himself.

Those in the extreme condition felt less social identification with the movement, less support for the protesters and less support for the overarching cause. Again, this happened for everybody, including liberals and anti-Trump people.

What’s more, the extreme protests caused those who supported Trump before seeing the videos to support him even more.

Other experiments included animal rights activism and pro-life protests. They all found the same thing; as extremism goes up, identification with the protesters and the movement and the cause (save for BLM) goes down and not just for those you’d expect; it goes down for everyone, including those who are more identified with and connected to the cause and movement.

- The reason is simple and involved at the same time – the acts are deemed immoral by everyone.

- That moral judgment undermines the pro, “in-group” bias that the movements supporters naturally have and

- reinforces the “out-group” bias of those who don’t naturally identify with the protesters, movement or cause.

- This strongly suggests norms of civility (morality) are more powerful than even our own alignment with fellow members of a group.

There is further evidence that many activists across a spectrum of causes are willing to engage in some form of “extreme” behavior and because their sense of moral conviction is so strong they are unable to see the behavior as extreme nor relate to those holding a more moderate view. Further, these same activists often see extreme behavior as increasing support for the cause.

- This perception gap between activists and non-activists further confounds the dilemma of deciding on the form and degree of a given protest.

- There may be instances where “extreme” acts increase or at least don’t lessen support, namely where the extreme action itself is deemed morally righteous and necessary, such as state sponsored mass killings or severely corrupt regimes.

- Another consideration is for movements to simultaneously emphasize the corruption and immorality of the targeted group while also directly and explicitly addressing why their actions aren’t immoral.

Kevin