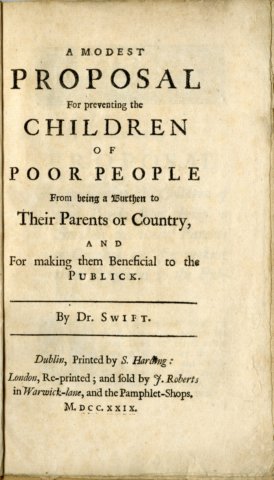

Channel Manager Incentives: A Modest Proposal

When a siloed staff is channel-structured and channel-incentivized, the knives come out.

Direct marketers who are measured against a net budget goal are loathe to give up “their donors” to major donor prospecting or try to drive them to events. In turn, Events folks want their walkers, bikers, gala goers, etc. to keep walking, biking, going to galas,with no “interference” from those who might try to turn them into institutional donors. And, of course Major Gift officers would prefer a clean field to solicit “their donors,” turning off the direct marketing that some major donors might prefer. And in the interest of maintaining their fiefdom, both online and offline channels can resist even the most basic of coordination like e-appends or asking donors about other preferred channels.

So how do you create incentives to share your toys with the other children? My modest proposal lies in transfer pricing.

So how do you create incentives to share your toys with the other children? My modest proposal lies in transfer pricing.

This is a concept in the for-profit world that recognizes transactions between and among business units. Think of a large oil company, for example, as two different companies: one that finds oil and one that sells oil.* In order to see how each business unit is doing, the overall company has to figure out the price at which a good is transferred (hence the name transfer pricing) from the exploration folks to the marketing folks.

The company is buying a good from itself to determine its value. This is the source, as you might guess, of much debate because a business unit’s success or failure hinges on the number that gets negotiated out.

So the modest proposal for nonprofits is to establish transfer pricing among various fundraising units and people. If the major donor officer wants a lead from the direct marketing database, they run the numbers and determine how much they are willing to pay for a lead. Because this “money” goes into the direct marketing coffers, proper incentives are built up for the direct marketing folks to acquire and nurture potential major donors.

Similarly, direct marketers know to the half penny how much they pay for a potential acquisition candidate from an outside list. How much are they willing to pay for an event donor “purchased” from the event organizer? Likewise, how much is the event runner willing to pay for a group of direct marketing donors who model out as likely walkers? We could see a much more orderly market in these donors, perhaps where 100 walkers are traded for 80 telemarketing donors plus a 7th round draft pick and a ream of copy paper.

And forget about doing e-appends simply because a multichannel donor does better for your organization than a single channel donor. Why would you do this when you charge the digital marketing manager per lead? After all, in this brave new world, they would now want to charge you per online donor when you attempt to attract their next gift offline.

The great thing about this is: 1) everyone gets to see either where market value truly is , or 2) who the truly great negotiators in your organization are. The market sets the price for the lead and you either pay it or you don’t. And if you don’t like the price, then you can try to acquire some other organization’s donors. After all, they may not have a cause connection to your organization, but it may be worth it to not have to try to pry potential major donors out of the iron grip of the person who runs your Charlotte fashion show event.

It’s only when donors are a commodity with a chattel price that we will understand how important they are to our organization or, more importantly, our various fundraising units.

Because the only alternative – setting goals for joint work rather than channel work, working together with your co-workers, realizing that your cause is a common good to which everyone should strive, and focusing on the donors’ wishes and what optimizes their experience and giving – seems really hard. Bring on the markets!

Nick

* My wife, who is brilliant and has a master’s in energy policy, would want me to note here that everything that I’m saying about the oil business here is vastly oversimplified. It is. There’s a reason for that: I don’t entirely know what I’m talking about. To the extent that I do, there are details like the multiple business units of an oil conglomerate and the different types of oil and such that don’t bear on telling a decent story. These details have been taken out back and shot.