Compared to what?

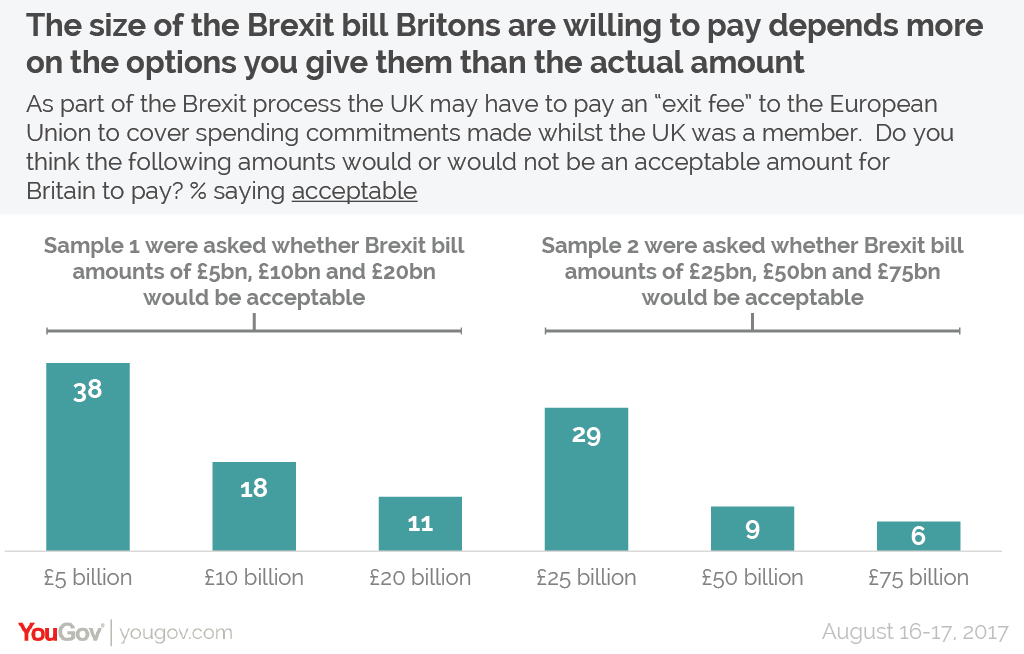

Two polls of Britons came out last fall. One said that only 19% of Britons were willing to pay at least 10 billion pounds in EU “exit fees” as part of Brexit. The other said 29% were willing to pay at least 25 billion pounds.

Here’s the weird part: these polls don’t conflict. Rather, both show the truth: no one has a fixed price in their head they are willing to pay. Rather they judge based on the options they are given. Here are the full results with credit to YouGov.Uk for the poll and graphic:

This brings up an uncomfortable truth: humans have no concept of absolute value. All our value perceptions are relative. This makes for some weird, but human, outcomes. For example, people would rather be paid less (but more than their neighbor) than paid more (but less than their neighbor). Hence the idea of keeping up with the Joneses.

You can use these quirks in thinking in several ways in your fundraising, including:

Ask strings. In our magnum opus on the science of ask strings, we talk about how your ask string, especially the first value in your ask string, anchors your donor’s gift. This is especially true for acquisition pieces where donors may not know what the “appropriate” amount is to give. Our ask strings act as a guide.

We strongly recommend the full white paper, but there’s one relative frame to try we wanted to highlight…

Positioning against a hedonic good. Framing your donation about against a good that gives pleasure can make people more likely to donate. This study tested this notion of relative value. In each test, there was a control with no reference point, a hedonic (related to pleasure, usually with no socially redeeming value) reference point, and a utilitarian (practical) reference point.

So for example, they asked people to donate $1 to UNICEF. People who got the hedonic version had the ask followed by “One dollar is the cost of downloading one top-ten song off of iTunes, such as the current #1 hit ‘Hallelujah’ by Justin Timberlake.” (Which dates this paper very nicely; the utilitarian option was MIT Professor of Physics Walter Lewin’s lecture, ‘Electricity and Magnetism,’ which is, of course, timeliness.).

Less than half (47%) of the of the control group donated, 57% of the utilitarian folks donated, and a whopping 88% of hedonic folks donated.

This also works for volunteering. Here, two hours was either “how long it takes to watch the season finale of MTV’s Jersey Shore” (hedonic) or “to watch the season premiere of House” (utilitarian). Before I go to the results, I’ll donate any amount of time you want if the only alternative is to watch Jersey Shore. (And they pre-tested this notion and found that Jersey Shore was viewed as much more hedonic than House.)

In this case, 12% of the control group volunteered, 14% of utilitarian folks volunteered, and 30% of hedonic folks volunteered.

Same donation amount. Same two hours to volunteer. Vastly different donation rates based solely on the framing.

Small versus large numbers. We’ve talked previously about the identifiable victim effect and how one person’s story is more valuable than statistics. At DonorVoice, we’ve also recently seen the opposite: two counterexamples using our pre-test tool where statistics did as well as an individual victim’s story. What gives?

In both cases, the winning statistics were brought down to a unit – one in six children or one in 11 adults has this disease or goes hungry at night. Instead of 11 million this and 19 million that, they brought down the statistics to the level than an individual person could make a difference. And that makes a difference. Like with Brexit polling, people don’t have a number in their head of people who need to be affected by a problem before they donate. Rather, they want a problem they can take a bite out of.

Interested in more fundraising information like this? Please subscribe to our newsletter here: