Learning from Politics: Chip In Change for Change

You’ve seen the headlines: “Americans more divided than ever”, “Gridlock reaching threat level crimson, which is worse than red somehow”, and “Pelosi-McConnell West-Side-Story-style dancing knife fight leaves two dead; four injured.”

The two major parties here in the United States seemingly can’t agree on anything.

But here’s a ray of hope. They can agree on donors chipping in.

Just glancing around, you have both Beto O’Rourke:

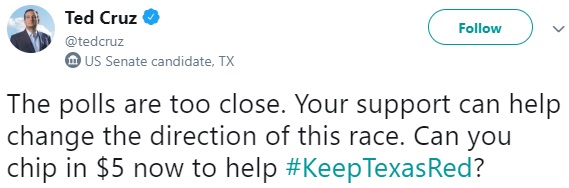

And Ted Cruz:

In Tennessee, you have Marsha Blackburn:

And Phil Bredesen:

I could go on and on, but I won’t for a simple reason: I don’t wanna. There’s only so much Googling a person can reasonably do on the subject of campaign asks. If you doubt me, just Google “Chip in $5”

This isn’t a new technique. Part of its popularity probably stems from the vaunted Obama digital campaigns testing into it. (And if you are unwilling to test, the next best thing is to steal from someone who tests.)

But very few nonprofits are using this language. Why, other than the Obama Effect, have political organizations almost unanimously adopted this language?

“Chip in” sounds very small. Giving permission for small donations increases the likelihood of giving, going back to Cialdini’s studies. He found that the phrase “even a penny would help” increased giving in a face-to-face environment from 28% to 50% (it was a different F2F environment back then). One could argue that the success of March of Dimes in their original launch was in part a variant of this. Although a dime meant much more then, it still was a way of giving permission for lower level gifts. Making a cost sound small decreases the psychic pain someone feels from making a purchase or donation.

The phrase fails Kant’s categorical imperative: if everyone did it, it would not help. Your penny would be eaten up by credit card fees, postage, and acknowledgments. But the evidence is that people give significantly more than a penny. While average gift did decrease, the total revenue from the canvass went up 64% because of the increase in response rate.

“Chip in” implies others are doing the same. In fact, The Oxford Dictionary defines “chip in” as “contribute something as one’s share of a joint activity, cost, etc.” Social proof is a powerful persuasive force. Knowing that others are doing it and are counting on you too can greatly influence decisions.

People like to be a part of something bigger than themselves. This is especially true for causes, political or nonprofit. The ability to make something part of your identity that ties you into a larger in-group can be very powerful.

The value of a name in political spheres far exceeds just their donation value. A $3 donor is also a voter at worst and perhaps a volunteer or district captain. And of course, they may be able to give more in the future. A $2,700 donor is these things, plus someone who may be able to attract like-minded funders at a max level.

I say this occurs in political spheres. But isn’t this true for your nonprofit as well? You want that $3 donor as a volunteer, walker, bequest donor, monthly donor, etc. And yet we generally have higher online ask thresholds and don’t use this type of validation of small gifts.

Should you do this all the time and for everyone? Absolutely not.

M+R tested $5 asks with ten clients. Seven raised more; three raised less. Also, this technique worked better with lapsed donors and prospects than with active donors. As they put it: “recent donors … don’t need the bar lowered the same way that lapsed or prospective donors do.” This is also what we reported in our ask string white paper – press your ask upward with active donors and retreat to lower values to renew lapsed donors. I also know of one organization that found success with a $5 ask and using positioning against a hedonic good (e.g., “you can achieve X for less than the price of your morning coffee.”); this has also proven successful as seen in the academic literature.

In short, this strategy makes sense for a certain type of audience using carefully crafted behavioral science cues. Personally, I’d wait until after the second week in November to try it, but it’s a technique whose time may have come for nonprofits.

Have you had any experiences? Please chip in your thoughts below.

Nick

P.S. I swear, while writing this, I got an email from a campaign-adjacent organization asking me to chip in $3…

“And if you are unwilling to test, the next best thing is to steal from someone who tests.”

Bravo, Nick. Well said.

But unless I’m missing something in the M+R testing, what happened NEXT? How were those $5 donors stewarded? How did the orgs in question make those donors feel that their $5 actually made a difference? That the org in question was actually GRATEFUL to get it? What systems did these organizations have in place?

What a great test for your lapsed donors. But not if you haven’t changed the internal systems that may have caused these donors to lapse in the first place.

I’m with Pam…Steal. The majority of nonprofits in the US of A can’t afford to test much … if at all. I figure that’s one reason why consultants exist. Our job is to TEACH and INFORM because we’re the ones who are supposed to be reading constantly and consistently and passing on information.

(And because I know Roger and his “politics” — Check out the stunning “poem” on twitter @Larisa_a about the Kavanagh hearings.)

Very interesting! I am getting a ton of these emails myself from my favorite candidates.

I think the “chip in” approach could work particularly well with nonprofit Giving Days.

Or on Giving Tuesday when there is a lot of social energy around giving to nonprofit causes.