Plastic Bag Bans and Your Fundraising Problem

The common fundraising bias is to focus on small problems, easily reduced – the conversion on your landing page, the response rate on your control mailing.

This last mile focus means we often miss related, larger behavior problems – i.e. the upstream problems.

Is the larger conversion problem tied to overfishing the same acquisition waters, the catch and release nature of list rental and co-ops and the copycat nature of appeals (e.g. the survey mailing, the nickel package, the front end and back-end premium offer)?

What’s more, our approach to solving problems, last-mile or otherwise, is heavily influenced by factors that have nothing to do with content, or user-experience, or context, or choice architecture. Instead, our experiences influence our perception of what’s possible or even conceivable. In other words, our problem solving style greatly limits and biases our answers and outcomes.

This is our plastic bag problem.

The Plastic Bag Problem

Forty some years ago plastic bags became the standard in US grocery stores. Predictably, disposing of them became a huge problem. They fill up landfills, cause floods and kill wildlife. Consequently, bans were rolled out in cities and counties in the early 2000’s to “solve” the problem. Not to be outdone, California issued a statewide ban in 2016.

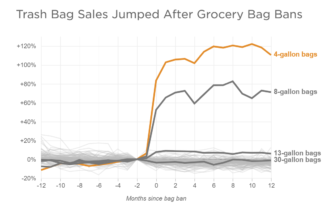

And plastic bags for groceries plummeted, leading to about 40 million fewer pounds of plastic per year. Small trash bag purchases and usage skyrocketed. Why?

The last-mile focus. The policymakers and advocates failed to consider the predictable ripple effects by ignoring consumers and how (plastic) bags get used – namely picking up after Fido, dog poop…

These purchased bags are thicker; and so 30% of the plastic waste savings was wiped away. Plus, paper bag usage skyrocketed, resulting in 80 million pounds of extra paper trash. And because the advocates and policymakers were so locked in to their preconceived views of plastic they failed to even consider a lot of studies showing paper bags are worse for the environment when you consider all the water and toxic chemicals and heavy equipment necessary to cut down and process trees. Bottom line, greenhouse gas emissions went up.

Your Reusable Tote Bag Won’t Get You Into Enviro Heaven

And no, the reusable tote bags aren’t going to come to the rescue. A UK government funded study found a cotton tote would need to be reused 131 times before it was better for the environment than using a plastic, grocery store bag. A Danish study was even more damning when considering more ripple effects from reusable totes; you’d need to use it 20,000 times to make it better than a plastic grocery bag.

What to do?

For starters, don’t reduce behavioral science to behavioral economics. And definitely don’t conflate the two. The latter is only a part of the former. Applying a behavioral science lens means a multi-disciplinary approach with expertise in cognitive psychology, behavioral economics, statistics, design and a commitment to spend much more time defining the problem than thinking up solutions.

Kevin

The trouble with the Danish study is that is that in calculating the number of “equivalent” plastic bags it effectively weights all the factors (water, climate change etc) equally. But they are clearly not, in fact, all equally important. So the 20k number is nonsense.

In other words even the study you cite as showing the problem of not defining the problem properly… is guilty of not defining the problem properly.

Living in CA at the time, I remember the ‘whole picture’ arguments being voiced loud and clear. To your over-arching point, the politicians didn’t want to hear it and only considered the short-term points they’d score with constituents. Not unlike turn and burn acquisition fundraising, the legislators had motives other than doing good in real terms. Rather, they were virtue-signaling with their votes.