REPEAT: Thanks, But No Thanks-Part 2

Thanks to everyone involved in the robust discussion here and on social media about the study of thank you calling on subsequent giving Kiki and Roger discussed Monday. In particular, discussion from Penelope Burk and other minds in fundraising have centered on who calls, when they call, and what is said.

I’ll have a brief aside about these factor at the end, but I want to home in on something Roger and Kiki brought up Monday that is the one area usually not covered: whom you call.

Let’s take a fictional donor: Ron S. from Pawnee, Indiana, who has generously donated a gold bar to your cause. Ron has, and his friends know he has, a strict ‘No Call’ policy: no phone use ever for any reason. Even if you get the who and what and when right, Ron will be turned off by your call and less likely to donate again. There is no good “when” for Ron.

Let’s take a fictional donor: Ron S. from Pawnee, Indiana, who has generously donated a gold bar to your cause. Ron has, and his friends know he has, a strict ‘No Call’ policy: no phone use ever for any reason. Even if you get the who and what and when right, Ron will be turned off by your call and less likely to donate again. There is no good “when” for Ron.

You have Ron’s on your file. This bears out in the Samek and Longfield study. People who don’t like getting phone calls and had a negative experience with that phone call had a subsequent $3 decrease in future giving.

This makes some sense. Giving flowers as a gift is a classic way of expressing gratitude, love, respect, and much more, so some say you can’t go wrong with flowers. But what if that important person in your life doesn’t like flowers. What you are saying by giving flowers to this person means that you either don’t know their preferences or don’t care about them. Specific preferences override the fundraiser’s general intent.

“We can assume some people don’t want to be called (or emailed, mailed) while others don’t mind. But we can’t presume to know who is who before picking up the phone.”

Conversely, about four percent of the people in the Samek and Longfield Study had a positive experience with their call and increased their subsequent giving. Getting the right who and what and when for them also didn’t matter – all you need with them is the right whom: the person who wants that call.

This means we need to be asking for donor preferences at the point of acquisition and beyond.

But let’s say you are somehow allergic to asking for donor preferences (and yet, somehow, haven’t broken out in hives from previous Agitator | DonorVoice posts). Is the whom still important?

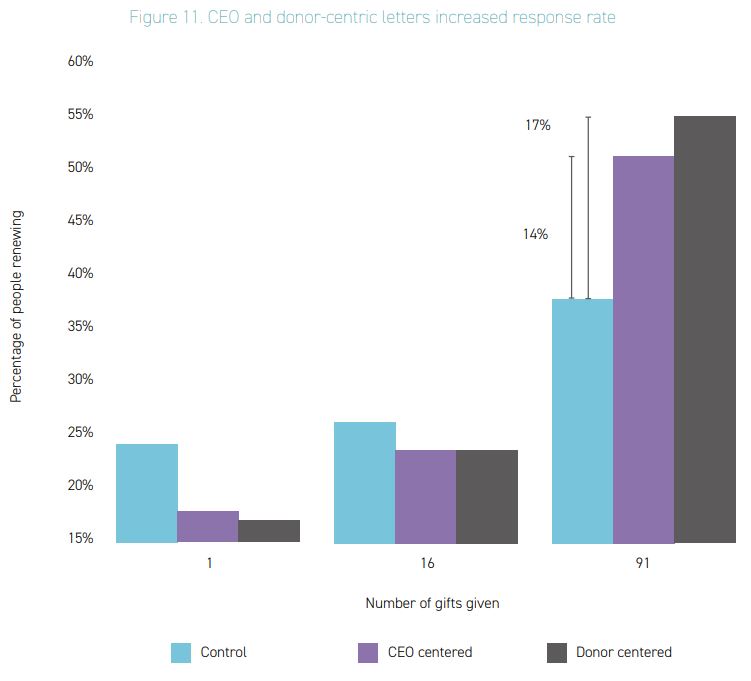

Yes, oh hypothetical rhetorical question asker, it is. In Shang, Sargeant, Carpenter, and Day’s Learning How to Say Thank You ebook as part of the Philanthropy Centre, they address the whom question with Iowa Public Television. They found that thank you letters significantly increased subsequent giving, but only among those who had already given more than 16 gifts:

From the researchers:

“The reason why neither letter worked for donors who gave less than 16 times is because these letters focus on “thanking the donor” as a person, not “thanking the donation”. It is only after donors developed a genuine relationship and felt as if they had “earned” this level of thank-you that their responses were uplifted.”

(And I would add that it worked in a medium of communication where there was already a pre-existing channel affinity, or at least tolerance, versus calling folks who may or may not want calls.)

So definitely read that study and digest what’s best to do when it comes to who makes the call, and when and what to say. But you can not be donor-centered or donor-focused or love your donor if you are implementing the same playbook regardless of the donor. A one-size-fits-all garment can cover, for better or worse, individuals based on what that size is, but it will never fit everyone equally well.

Now, my brief aside on the Samek-Longfield Study… As a fundraising community, we thought that calling by low-level staffers 3-7 months after the gift without knowing the preferences of callees with this particular script would work. Maybe you personally didn’t think this, but since that’s what the community of fundraisers thought on average, most of us are snowflakes in that avalanche.

Consequently, some of the “of-course-that-didn’t-work-because-X” is tinged with hindsight bias as to the reasons. I’m not immune – when I saw that we fundraisers had predicted an 80% lift in retention, I thought that was crazy high. But the study indicates that’s near the most likely lift I would have picked had I been asked.

It is great to be wrong. Here’s something that some were doing — with what it can be argued is the wrong who, whom, what, and when — and that some continue doing it despite the fact t doesn’t work. We can draw the lines around the parameters of what didn’t work as loose or as narrow as we want, but it’s still something we can stop doing, or test stopping doing it, or test doing it differently. Any road you take from that point leads to better.

In short, we learned something and you don’t learn things from being right.

It’s part of why I’m excited for our Which Half of Your Marketing is Wasted? webinar later today; there is great freedom in knowing what we no longer need to do. Let’s find what doesn’t work. Let’s burn it and use it as fuel for our journey forward. Let’s celebrate being wrong on the way to being more right.

Q: In this study, did people who were thanked give more than people who were not thanked?

A: Yes.

Those who were actually thanked, i.e., where an actual conversation occurred, actually gave more. Only one table, Table 6, reports the behavior of those who were actually thanked. They gave significantly more than those in the treatment group who were not reached.

The study focuses on a treatment in which only 30% of the people in the treatment group were actually thanked, i.e., where an actual conversation occurred. (The actual percentage thanked in each of three experiments was 26.7%, 27.5%, and 35.0%, see Table 5.) Those in this treatment group gave significantly more in one model (Table 3 Column 4), insignificantly more in three models (Table 3, Columns 1, 2, 5) and were almost precisely identical in the final model (Table 3, Column 3). Thus despite only a minority of those in the treatment group actually being thanked in an actual conversation, the only statistically significant result indicates that the treatment still worked. The treatment group effects were small, but then only a small proportion of the treatment group was actually thanked.

Q: Were the fundraisers estimations wrong?

A: No. (Or at worst, “We can’t tell.”)

The study description for the fundraisers’ was “Some new members were randomly assigned to receive a personal thank-you call.” A normal interpretation of this statement is “Some new members received a personal thank-you call. They were selected randomly.” The actual administration of the experiment was, instead, “Some new members were randomly assigned to be at a 30% risk of receiving a personal thank-you call.” If we interpret the statement the first way, then the fundraisers’ estimates may well be correct. If nothing else, they correspond with the only results provided regarding those who were actually thanked.