Six Golden Writing Rules

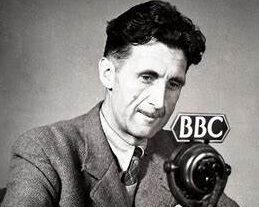

Eric Arthur Blair, better known by his pen name George Orwell, wrote, “Politics and the English Language” in 1946. He hated empty and obscure prose. His culprits were,

- Dying metaphors: essentially clichés, which “have lost all evocative power and are merely used because they save people the trouble of inventing phrases for themselves.”

We won’t attempt to redo the myriad lists of professional gobbledygook we all use that are a Google search away – e.g., “at the end of the day” anyone?

- Operators or verbal false limbs: these are the wordy, awkward constructions in place of a single, simple word. Orwell included “exhibit a tendency to,” “serve the purpose of,” “play a leading part in,” “have the effect of.”

Here are a couple other peeves – ‘relative to’, “due to the fact that”

- Pretentious diction: Orwell identifies a number of words he says “are used to dress up a simple statement and give an air of scientific impartiality to biased judgments.” A few that make his list, expedite, predict, ameliorate and utilize.

Any “noun + ize” combo is a prime target for poor word choice.

Any “noun + ize” combo is a prime target for poor word choice.

- Meaningless words: He considered “romantic,” “plastic,” “values,” “human,” “sentimental” abstractions because they don’t point to a discoverable object. He also hated political buzzwords as “democracy,” “socialism,” “freedom,” “patriotic,” “justice,” and “fascism,” since they all have several meanings that can’t be reconciled with one another.

This treatise got reduced down to his Six Rules that are as applicable today as 80 years ago.

- Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

- Never use a long word where a short one will do.

- If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

- Never use the passive where you can use the active.

- Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

- Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

His other advice worth heeding?

“Probably it is better to put off using words as long as possible and get one’s meaning as clear as one can through pictures and sensations. Afterward one can choose—not simply accept—the phrases that will best cover the meaning.”

An example of this is interviewing beneficiaries. You’ll want to guide this discussion ever so slightly but only with open-ended prompts. It’s a conversation. Record it and let the voices and verbatim wash over you before you put finger to keyboard.

Kevin

Lovely piece. And the ending part about a guiding philosophy for interviewing beneficiaries (and donors, I would add) is particularly inspiring. It’s all about the feelings and sensations “at the end of the day.”

Thank you Claire, much appreciated and always happy if we can create even a morsel of inspiration

Some writing rules we can’t hear too often. Just when we think we’ve got them down, we see old bad habits creep back in … sometimes in our own writing. Thanks for this helpful refresher.

Hi Willis, yep, writing is hard and lots of it is mechanical, which means we can all get rusty. Jack Nicklaus, arguably the golf GOAT, started every golf season by re-learning all the fundamentals, starting with the most basic, how to grip the club.