The Path of Continuous Improvement

Test ideas should, among other things, work backwards from the behavior one is trying to influence.

Sure, the brown kraft test envelope might do better than the plain white control, but why? And is it going to increase response rate or average gift? And is it better with everyone or just a select group and why?

Answers to these questions shouldn’t be arrived at with after-the-fact “fishing expeditions” through the data and the accompanying slicing and dicing. These answers should be arrived at ahead of time in the form of hypotheses – what we think will happen and why.

One thing is for certain, mail both envelopes and they won’t get the exact same result; one will ‘win’, one will ‘lose’. What is far from certain is whether that “finding” is all noise and no signal. If the idea is grounded in theory you’ve got extra validation if it wins – i.e. a reason to believe it wasn’t noise.

An Example

We ran experiments with UNHCR specifically aimed at the giving amount decision (i.e. average gift), which is a largely separate mental decision from the “do I give or not” decision that precedes it.

All our test ideas beat the control and as hypothesized; response rate was statistically the same, average gift was the difference maker.

We’ll share those findings in brief but the main point of this post is a nod to continuous improvement and incremental innovation because new evidence has surfaced about how to improve one of our test ideas that did beat the control but wasn’t the best performing test.

What We Did

Donors (subconsciously) perceive a cost and a benefit to giving, and there is plenty of evidence that how one presents the ask has a big impact on how fast the cost perceived by the donor rises relative to the donor’s perception of the benefit. If cost goes up faster than benefit, donors willl give a lower amount.

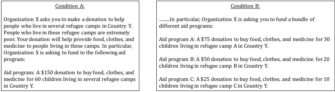

This initial, lab experiment from our extended, behavioral science unit team presented two conditions.

In the first, Condition A, after the introduction asking people to help refugees, the cost was presented as one lump sum of $150. In the second, Condition B, after the same introduction, the cost was presented as a bundle of different aid programs. In both conditions the perceived benefit (help for 60 children) and the amount asked ($150) were the same but in condition B the cost was broken down.

People were significantly more likely to donate in Condition B (71%) compared to Condition A (46%). The reason? People perceived the cost to be much higher in Condition A.

We did online donation page testing for UNHCR against the control, shown below. The control condition had each amount linked to a different tangible benefit for the refugees ($85 for a stove, $60 for a radiator, $45 for blankets). We call this an asymmetrical benefit structure, where a higher amount is linked to a completely different benefit.

Donors were randomly assigned to this or several test conditions, two of which we’re sharing here. The lead-in copy was the same, all that differed was the description of benefits for the refugees and the donation buttons.

Test conditions:

- Symmetrical condition. This presentation was selected to make the mental gymnastics of determining cost/benefit easier with cost rising commensurate with benefit. In the often used asymmetrical (i.e. shopping list) fashion it’s hard for donors to know if the heating stove is delivering $15 or more of additional benefit over the radiator ($60 ask amount). What they know for certain is their cost goes up.

- Bundling of the symmetrical condition. Can we increase the average gift by bundling together the cost side and making it seem like they are buying more benefit, namely a more direct mental linkage to the 9, 7 and 5 blankets.

- Aggregated: not shown but we did the math and put the $190 figure in the orange box ($85 + $60 + $45)

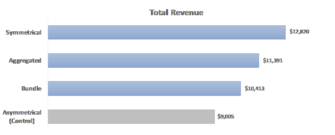

Results

This shows total revenue, but revenue per donor and revenue per page view all followed the same rank order. Also, conversion rates were statistically identical across all test and control conditions.

The Reason We Wrote This Post

Brand new research from the DonorVoice Behavioral Science Nudge Unit did more experiments on bundling and came up with the novel idea (driven by same theory) of bundling both the cost side and the benefit side. You’ll note from the test described above we only bundled the cost side in our test to lower the perceived cost.

In a nutshell, here is what they tested,

- Lump sum condition: Give $50 to help 20 children

- Bundle condition: fund a bundle of aid programs to help 12 kids at $30, 6 kids at $15 and 2 children at $5 (total amount of $50 to match lump sum)

- Bundling ‘benefit’ kid side: give $50 to help three groups, 12 kids, 6 kids and 2 kids

- Bundling of ‘cost’ side: Give $30, $15 and $5 to help 20 kids

- Bundling of both cost and benefit side: combo of #3 and #4

This latest research found that bundling either side beat the lump sum offer but that bundling both sides (#5) beat either separately.

The lesson in all this?

- Your test idea, if grounded in theory, may fail, but it’s one execution or application.

- Your test idea, if grounded in theory, may win, but it’s one execution or application.

In either case, keep leaning on the foundational bedrock of theory, dig deeper and think differently, creatively even.

And if your test idea isn’t grounded in theory, ask yourself why not? Having a solid foundation for spending organizational time and money sure beats the scattering resources on shifting sands.

Kevin and Kiki