The Strength of Knowing What We Don’t Know

Kevin’s moving tribute to his father noted two essential traits for greatness in any profession –including fundraising:

“He had a voracious appetite as a learner. As smart as he was, his greatest strength was his humility in knowing the vastness of what he didn’t know.”

We all need to work harder at harnessing the immense power of knowing what we don’t know. Failure to tap into that power is what results in continual repetition of many practices that when repeated over and over turn too many fundraising programs into the equivalent of a nearly petrified forest.

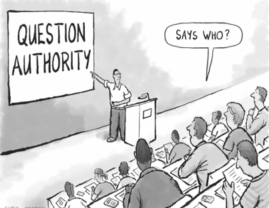

Too often petrification in fundraising—the inability to adapt and failure to grow—is touted as a ‘best practice.’ In reality what are often labelled as “best practices” are merely the accretion of years and years of unchallenged myth and belief passed along from fundraiser to fundraiser without evidence or challenge.

From the way files are segmented, ask strings created and third-party data misapplied in the creation of fundamentally useless personas, to the unproductive use of one-size-fits-all messaging and the mail-more-make-more mentality ours is a $400 billion industry powered by too much anecdote and not enough by doubt, curiosity and the “voracious appetite of a learner.”

There are lots of reasons for this. Most pronounced I suspect is that most organizations don’t have cultures where folks feel comfortable or safe in challenging the status quo. Add to that an industry-wide history where eminence of some consultants often occludes actual evidence and where too many defer to a senior colleague who says, “I think this is the best way to do it.”

There are lots of reasons for this. Most pronounced I suspect is that most organizations don’t have cultures where folks feel comfortable or safe in challenging the status quo. Add to that an industry-wide history where eminence of some consultants often occludes actual evidence and where too many defer to a senior colleague who says, “I think this is the best way to do it.”

Survival and growth given today’s acceleration of change requires that we move from a culture of “I think” to one of “I know.” And the “I know” must be prefaced by the question, “How do you know?” and the proof behind the knowing produced.

If we can make it psychologically safe in our workplaces and among each other to more often ask the question “How do you know?” we’ll not only speak up in the presence of “experts” who claim to know the answers, but we’ll be more willing to deviate from the petrified status quo and take more calculated risks. Risks that lead to growth.

It all starts, of course with the humility to admit and face what we truly don’t know. Then, in a nonjudgmental, straightforward way express our curiosity in a manner that doesn’t put people on the defensive.

I didn’t know Kevin’s dad. I wish I had because I would have asked him what questions he used to access the vast unknowns.

Fortunately, I do get to work with his son and here are some of the questions we regularly ask of each other and folks we work with when dealing with recommendations for the organizations we serve:

- What are the advantages of this recommendation?

- What are the disadvantages?

- Why did you make this assumption?

- Why do you think it’s right?

- What’re the consequences if it’s wrong?

- What parts of your analysis are you uncertain about?

What questions do you ask that tap into the power of the unknown and trigger your curiosity?

Roger