What happens if you listen to your donors TOO POORLY

Let me get this out of the way first: I’m a Jeff Brooks fan. I grew up in direct marketing with his Fundraising is Beautiful podcast* and Future Fundraising Now blog. I’ll always remember my first blog post where I said to my wife that Jeff Brooks linked to me in the same tone of voice that a tween girl thinks that Justin Bieber looked RIGHT AT HER! And I also have an oft-read copy of The Fundraiser’s Guide to Irresistible Communications, as you can see at right. It’s definitely from today.

Let me get this out of the way first: I’m a Jeff Brooks fan. I grew up in direct marketing with his Fundraising is Beautiful podcast* and Future Fundraising Now blog. I’ll always remember my first blog post where I said to my wife that Jeff Brooks linked to me in the same tone of voice that a tween girl thinks that Justin Bieber looked RIGHT AT HER! And I also have an oft-read copy of The Fundraiser’s Guide to Irresistible Communications, as you can see at right. It’s definitely from today.

(I don’t yet have How to Turn Your Words Into Money, but it’s on my Amazon Wish List, for those who were wondering what to get me for Christmas.)

But I must speak out on his Friday blog post, where he posited, along with Virtuous blog, that Walmart had gone astray to the tune of $1.85 billion because it listened to its customers too much.

The story goes that Walmart listened to customers who said they wanted less cluttered shelves, so they did that in Project Impact and lost money. From this, the alleged lesson is that Walmart listened to its customers too much and, likewise, we shouldn’t listen to our donors when they tell us what they want. To quote from Jeff’s piece:

“Ask them what they want, and they’ll give you all kinds of terrible advice. They want to hear from you once a year. They don’t need emotional stories or suggested ask amounts. They don’t want long messages or emotional photos. They tell you they’ll donate more if you don’t do those things.”

Here’s where I differ: these are not examples of listening to donors too much. These are examples of listening to donors too poorly.

Let’s take the Walmart example for a moment. There are three cardinal sins in the research that Walmart seems to have done here:

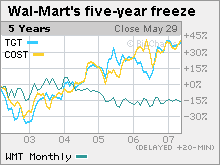

1. They got target fixation. Or, in this case, Target fixation. Here are the stock changes for the five years preceding the decision to declutter shelves.

TGT is Target. During this time Target was growing significantly compared to Walmart. So Walmart had the idea “hey, let’s be more like Target” and they tested that, rather than listening to what their customer said. Good Experience puts it well in their blog post on this:

“The mistake was a lack of customer focus. I know, I know: “They ran a survey! Customers loved the idea!” But that’s exactly the problem. Walmart didn’t pursue the question of what customers wanted. Instead, Walmart came up with the answer first, then asked customers to agree to it. That’s exactly the wrong thing to do, because it ignores customers while attempting to fool stakeholders into thinking that the strategy is customer-centered.”

With nonprofits, this can often happen with new leadership. People will come in and say “we need to change things up and be more like X,” whether X organization is anything like your organization or not. Then surveys are done with that conclusion in mind. As a result…

2. They surveyed for the wrong thing. I have not seen the surveys on this, so I can only guess based on the reporting. But it sounds like they asked whether people would like it if they would declutter the aisles and shelves.

What they should have done is looked at shoppers’ commitment to shopping there and the amounts they spend, then also asked what people’s ratings are for various aspects of their customer experience. From there, you can use statistical methodology to determine what actually drives commitment and behavior. That’s what we do with our commitment studies. It’s the way of getting results that matter, without…

3. Pony thinking. There’s probably a technical term for this, but what I mean here is if you ask an eight-year-old whether she wants a pony or not, she will likely say yes. If you pair this with the question “How committed are you to cleaning up large piles of poop for the rest of your life?”, that goes down significantly.

Likewise, if you have a survey audience or, worse, a focus group and ask them if they want less cluttered aisles, they will say yes. The survey recipient doesn’t know the trade-offs that go on.

But for Walmart, “less cluttered shelves” also equals “fewer items you may want to buy.” You can’t survey one without the other. There is a story, perhaps apocryphal, about a Walmart executive bringing two bags of groceries into a board meeting that she bought at another chain supermarket because she could no longer get them at Walmart.

By the end, Walmart had presentations like this one that had “less inventory” as an end itself, rather than as a means to achieve greater satisfaction. “Great selection” isn’t in there. So the person who made less cluttered shelves and made the Walmart executive shop at another store was doing what they were given incentives to do.

And for nonprofits, if you look at traditional surveys, people will say they want fewer communications and more information on the impact of their donations. These often oppose each other. If you look just at taking away communications, without making sure you are connecting better with the communications you do have, you will likely experience loss.

But if you do what several nonprofits have started to do now (e.g., Union of Concerned Scientists) where you announce that you are decreasing communications based on their feedback, ask for additional feedback, and make each piece more focused on the donor, you will hit your year one goals and be raising more money in year two, free of the volume rat race.

There are plenty good examples of bad surveys – Kevin has done a great piece on what surveys work when and how here. And if you take the data from those surveys (e.g., people saying they only want happy stories), you are going to get bad results, just like Jeff says.

However, the problem isn’t that we are listening to the donor; it’s that we are doing it poorly. Using any test results where people are asked to compare pieces like DonorVoice’s multi-test tool, you can measure both conscious and subconscious cues, getting to a deeper understanding of the donor and what makes them tick.

So, I greatly respect Jeff, but the very title and idea of Jeff’s post – “What happens if you listen to your donors TOO MUCH” – is actually the opposite. We think we know donors from one line on a survey (or less!) when we should be listening to them more, more correctly, and more deeply.

* I also applaud the choice of Holst’s The Planets for its theme song; although I prefer Mars to Jupiter, the latter is a more effective podcast theme song.

** A funny post-script: as I was writing this, the New York Times posted a piece about the new Walmart. They are paying their employees more and giving them the ability to rise through the ranks. They are also receiving more training on customer service. Survey results on “clean, fast, friendly” scores have increased for 90 consecutive weeks and sales are up 2% over the general merchandising average. Profits are down six percent because of these labor costs and other investments, but my guess is that Walmart is playing a longer game to try to retain their customers.

Hi Nick

I am a boutique independent agency based in Australia ie not a competitor but certainly we are singing from the same song sheet. A bad experience with a survey (that unknowingly was poorly designed) can really turn off fundraisers from researching their donors …and, collectively, word of mouth is pervasive which in turn shapes overall attitudes to listening to customers. Unfortunately this can made fundraisers even more controlling when they do research in response to management or external pressures. So for many, there is a catch 22 dynamic. Which in the end means distrust in listening too closely to donors..instead of listening more openly. Best wishes, (Dr) Kym Madden

Absolutely! It’s tough to believe in surveys when there is so much chaff with the wheat. Personally, I’ve been burned by poorly designed surveys and surveys that were designed with an agenda (that is, put out this survey to prove what the HiPPO — highest-paid person’s opinion — already is). As humans, we don’t know how much we don’t know about our own opinions. Thus, surveys and focus groups that focus on that are going to come out wrong — Jeff’s original piece isn’t wrong about that.

I would say that if someone has challenges about trusting surveys, I’d encourage them to sit down with folks who design scientifically valid surveys, who can take you through exactly why they/we are doing what they are doing. And they will have the same stories of bad survey designs that you do (I remember an employee survey where I looked at the results to the survey “Do you think this workplace will change as a result of this survey.” People who loved working there said no, as in “No, this place is perfect!”; people who hated working there said no, as in “No, this place is horrid and incapable of saving itself.”). The difference is that you can correct for these flaws and get better results as a result.

I break down donor feedback primarily into 2 buckets.

1. Donor verbatims – what you’ll learn from surveys, face-to-face meetings, calls, etc.

2. Donor digital body language – what you’ll learn from their actions (donations, volunteerism and, most importantly, tracking of their online engagement including clicks, time on site, views of videos, etc.

Verbatims are helpful to get things started with your research but digital body language is truth serum.

Definitely – you want to make sure you are also looking at activity. However, I wouldn’t say that it begins with verbatim and ends with digital body language — the two mutually reinforce each other.

Take as an example a volunteering ask. Who is more likely to volunteer: someone who has volunteered before or someone who hasn’t? Obviously the first.

Now, let’s say you can layer on survey data. Who is more likely to volunteer: someone who has volunteered before and hated the experience? Or someone who just joined the organization and said on surveys that they’d never volunteered before, but that they would love to start? Obviously the second person.

The trick is that if you look only at activity data, the first scenario and the second one are the same. Activity can tell you what people do, but not how they feel or felt about it. And it isn’t just for volunteering — people are less likely to donate online again if they had significant trouble on the form.

That’s why feedback is so important not just to get research started, but also to continue throughout the process, informing the “what happened” with why it happened and how they felt about it.