When Progress Isn’t Enough: The Risk of Public Goals in Fundraising

One of the greatest movies of all time for those of us who enjoy parody, slapstick and juvenile humor is Will Ferrell’s Talladega Nights.

He spends most of his life against an impossible standard of “if you ain’t first you’re last”, a motto from his father who was high on peyote at the time he said it. In a moment of “caring”, semi-sobriety the father notes the credo is ridiculous as there is very clearly 2nd place and 3rd place.

But, there is many a contest where nothing after 3rd place is recognized – Gold, Silver, Bronze, everyone else failed equally here. How many charities out there state an objective goal for impacting their cause with pledges to reduce [insert something crappy here] by X% by Year Y.

What happens when society or your organization or the government falls short? How do people react? Is it the “if you didn’t succeed, you failed” equivalent of Talladega Nights? Yes, it seems so.

Researchers looked at eight different scenarios ranging from people fighting addiction to students trying to improve their grades to companies trying to get more diverse or reduce carbon footprint to nonprofits fighting poverty and climate change.

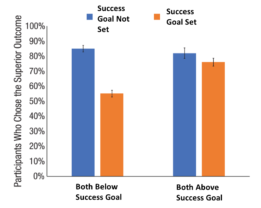

In every scenario participants learned about two people/companies/NGOs, focused on the same goal and both having been rated on their progress after one year of effort. The ratings were numeric values from 0 to 100. The experimental conditions included,

- Both entities with low scores but one always objectively higher than the other – a 0 to 20 and the other 20-40 (so one in green, one in purple) and no stated, objective success goal.

- Both entities with low scores (one objectively higher than other) and a stated objective goal that was always in the gray bar (40-60)

- Both entities with high scores but one always objectively higher – a 60 to 80 and 80 to 100 (so one in yellow, one in blue) and no stated, objective success goal

- Both entities with high scores (one objectively higher than other) and a stated objective goal that was always in the gray bar (40-60)

Every scenario posed the same question. “Which entity did better or did they both do about the same?” Realize the objectively correct answer is sitting right there based on the outcomes scores, one was always higher than the other. It should be 100% picking the entity that got the higher score.

But, the height of these bars is the percentage who correctly picked the higher scoring entity and none goes up to 100%. That means human nature intervened. We humans have a big, negative lumping bias when an objective, often numeric goal is set – the orange bars.

Only slightly more than half give credit to the entity that did better on a relative basis when both still fell short of the goal. If you didn’t achieve your goal, you failed. Ouch. The upward positive lumping bias doesn’t exist. If both achieved the goal we still give extra credit to the one that did better.

The fundraising takeaway?

Be careful with public goals. When you hit them, great. But if you fall short—even slightly—you risk losing credit for what you did achieve.

Instead of rigid numeric targets, consider setting directional goals with context. Show progress. Tell stories. Highlight what changed and who benefited.

Fundraising is not the Olympics. If you helped 49% of people instead of 50%, that’s not failure. That’s impact.

Often, the victory is real with demonstrable progress improving many lives and yet, if we missed by an inch, we missed by a mile it seems.

Kevin