Why Measuring Donor Satisfaction Isn’t Enough

The great German philosopher, Immanuel Kant, argued knowledge cannot come from raw, sensory input alone; there must also be pre-existing, mental categories to sort and organize the sensory information. A modern-day Kantianism for our world is Data without theory is blind, but theory without data is empty.

Let’s tackle the first part of this maxim by working through a concrete example—donor satisfaction.

Being satisfied is a desirous state. And on the surface, absent theory, it would seem the best way to know if a donor is satisfied is by turning the concept (of being satisfied) into the measure with a single question like, “Overall, how satisfied are you with <fill in the blank>.”

But what exactly do we mean by “satisfaction” and, perhaps more importantly, “dissatisfaction”?

Imagine we asked donors about their satisfaction after an interaction with a telemarketer. There are many reasons why a telephone conversation could lead a donor to feel satisfied. For example, the telemarketer could have given a really inspiring rationale when asking for support. Or maybe he or she were personable and pleasant. Similarly, there are multiple ways a donor can be left feeling dissatisfied; an annoyingly pushy telemarketer, an inauthentic, stilted, overly-scripted conversation, or insufficient information about the charitable cause.

Notice how each of the satisfaction/dissatisfaction reasons provides different, practical insight about a campaign’s strengths and weaknesses. If you learned that an ask/pitch was inspiring and promoted donor satisfaction, you could take steps to replicate that success in your next campaign. If you learned that your telemarketers were too pushy, you could remedy that problem by making appropriate revisions to the script and training.

Obtaining pinpoint, prescriptive guidance requires asking precise questions about the donor experience. But where to start? How to parse the concept of satisfaction?

Two interrelated problems arise at this point. The ‘infinity’ problem of so many ideas and possible questions to ask, with the vast majority being random noise, not signal. The Kantian solution? A theory of donor experience. A lack of a unified theory or set of theories is the crux of a lot of negative sector trendlines (retention, acquisition rates) and inefficiency. Theory provides a shining light through the infinite possibilities that are mostly cluttered with dead ends.

It’s the reason why DonorVoice, in its ongoing effort to evolve our evidence-based practice and yours, has looked to the field of human motivation to further crack the code.

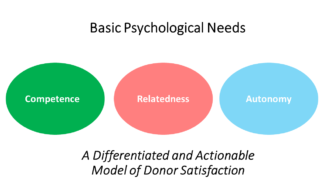

Over forty years of research and theory shows people have three basic psychological needs and satisfying these promotes optimal qualities of motivation and feelings of wellness. These needs are,

- Competence – feelings of effectiveness. For donors, it could mean feeling like they’re making a positive difference. It could also mean learning something new, for example, the problem your charity is trying to solve.

- Relatedness – feelings of being connected and having a sense of belonging with others. Giving and contributing to others is one way people to satisfy their need for relatedness. But how much relatedness donors will actually experience depends on how well your campaigns can foster a meaningful sense of connection between them and both the people receiving their support and your charity. Touchpoints that are plainly role-bound, transactional, and empty of interpersonal salience are not likely to promote a sense of relatedness.

- Autonomy – feelings of willingness and volition. For donors, this first and foremost means not feeling guilted or otherwise pressured or into giving. Providing a convincing rationale, along with meaningful options for choosing how to give support are ways to increase donor autonomy satisfaction.

The more donors feel a sense of competence, relatedness, and autonomy when engaging with your organization, the more likely they will be to commit to your charity for the long-term.

We’ve started measuring feelings of competence, autonomy, and relatedness and have found it gives a much more nuanced, prescriptive set of insights than the typical “satisfaction” measures.

By assessing the need satisfactions that foster optimal qualities of motivation we’re able to better understand the donor experience and let you know what you’re doing well and where you stand to improve.

For example:

- Donors feeling ineffectual or hopeless in promoting a human rights outcome (low competence) after a telemarketing or canvassing interaction (and despite saying “yes” to the ask) means these specific donors need enhanced feedback about how their gifts are making a positive difference. But send that enhanced feedback to those with high competence and you risk violating the “show me you know me” maxim of good donor communication.

- Donors feeling unduly pressured or guilted into giving by a pushy canvasser (low autonomy) means those donors (and only those) would benefit from a non-pressurized, “save call” designed to provide more rationale for your charity and their choice.

- Donors feeling unappreciated and taken for granted (low relatedness) warrants an apology to mitigate the negative interaction but only for whose relatedness needs were thwarted.

Zero-party data is the only data that can tell a fundraiser what its donors are thinking, feeling, and doing. But, for fundraisers to act they need to reliably know why donors think, feel, and behave as they do. Finding quantifiable and actionable “why answers” starts with asking the right questions.

So, what theory of charitable giving are you using to guide your data collection?

Stefano