Beware of Psychological Reactance

“Tug on donors’ heartstrings…”

“Make them feel pain and sorrow… “

“Guilt them into giving…”

“We want donors to feel like giving will bring them closer to God’s heart…”

“The quickest route to connection is fear and pain…”

“By giving, donors will get relief from their emotional discomfort…”

If statements like these characterize your approach to fundraising, I’ve got some bad news for you: psychological reactance is likely causing your campaigns to backfire.

Sure, you may be able to snag some donors for a one-off. Some of those might even give again. But, you’re impeding your progress toward building a community of satisfied and committed long-term donors—the true measure of fundraising success.

Why? Because statements like these could trigger psychological reactance.

“Reactance” is a term psychologists use to describe people’s reflex-like tendencies to rebel against situations that threaten their perceived freedom and, in some cases, to do the opposite of what’s being suggested. If you’re thinking of teenage behaviour right now, you’re spot on!

People don’t like to be pushed around—I know, I know, big surprise! People are also pretty good at detecting a manipulation. They may not be able to articulate exactly how they’re being manipulated, but they can certainly feel it.

When people are made to feel unduly pressured to do something, two reactions are typical.

- They resentfully comply—and I wouldn’t bet on these donors giving in the future, no. These donors are going onto your “lapsed” list; OR

- They react by angrily taking steps to restore their autonomy … and one way to rebel against a control is to do the exact opposite of what the persuasive messaging intends. In fundraising, this could mean tossing your mil into the trash or deleting and unsubscribing from your emails. What the kids these days call an “epic fail.”

Consider the following study. It doesn’t come from the fundraising domain but it makes the point very well. The researchers compared two different types of motivational interventions that aimed to reduce prejudice.

They created two anti-prejudice brochures. One was autonomy-supportive: it emphasized personal choice and explained why prejudice reduction is important and worthwhile. The other brochure was controlling: it urged people to combat prejudice by complying with social norms of non-prejudice—exactly the type of message you’d expect to elicit reactance.

The excerpts below will give you a sense of how the messages from these two brochures felt to readers.

| Autonomy-supportive | Controlling |

| You are free to choose to value non-prejudice. Only you can decide to be an egalitarian person… In today’s increasingly diverse and multicultural society, such a personal choice is likely to help you feel connected to yourself and your social world… | In today’s multicultural society, we should all be less prejudiced. We should all refrain from negative stereotyping. It is, after all, the politically and socially correct thing to do, and it’s something that society demands of us… |

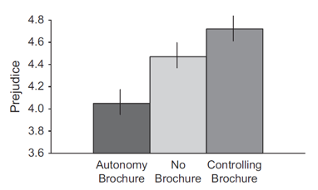

University students were randomly assigned to receive one of these brochures as part of a campus initiative to reduce prejudice. There was also a no-brochure condition in which participants read motivationally-neutral information about prejudice. After going through this material, participants’ prejudice was measured with a standard questionnaire. Here’s what the results looked like.

Yep, you’re seeing that correctly: While people who received the autonomy-supportive brochure showed less prejudice than those in the no-brochure condition, people who received the brochure with controlling messages showed more prejudice than those in the no-brochure condition.

In other words, the controlling brochure that was filled with pressuring shoulds and demands produced the ironic effect of increasing prejudice—classical reactance!

There’s more to the story.

Participants also completed a questionnaire probing their reasons for reducing prejudice. Participants who read the autonomy-supportive brochures agreed more with statements like, “Striving to be non-prejudiced is important to me” than they did with statements like, “I would feel guilty if I were prejudiced.” Importantly, this pattern of response partly explained why participants who received the autonomy-supportive brochures showed less prejudice.

Clearly, these lessons can be applied to fundraising. We don’t want donors to support a cause out of guilt or pressure. What we do want is for donors to support a cause out of an understanding and acceptance of the importance or worth of the charity. In other words, we want them to give because they want to, not because they feel they have to.

That’s easier said than done.

Developing an autonomy-supportive campaign, one that promotes donors’ feelings of choice and volition, requires thought and effort. There’s no way to get around that, I’m afraid. That’s the bad news. The good news is that it’s feasible and well worth the effort because autonomously motivated donors are in it for the long run. Autonomy support is a big topic and I’ll take it up in my next post.

For now, let’s stop shooting ourselves in the foot by remembering to beware of psychological reactance.

Stefano

P.S. References

Brehm, S. S., & Brehm, J. W. (1981). Psychological reactance: A theory of freedom and control. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Great stuff. I wonder where FUD https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fear,_uncertainty,_and_doubt and FOMO https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fear_of_missing_out fit.