The Double-Edged Sword of Social Proof in Fundraising

Social proof is a psychological and social phenomenon whereby individuals tend to emulate actions and behaviors of others to shape their own. It’s grounded in the belief that if many people engage in a certain behavior, it must be beneficial or correct, thereby prompting others to follow suit.

Here’s an example fundraising message, “On average, our supportive donors contribute $50 to help keep our services running. Will you join them in making a difference?”

This raises a vital question: does this work or might it backfire by creating undue pressure on potential donors?

The DonorVoice Behavioral Science team conducted an experiment to shine some more light.

There were three conditions:

- Control – participants received no social proof

- Social proof – informing donors about the typical donation amount

- Negative social proof – donors were told that most people, in fact, do not donate.

The “negative social proof” condition might be familiar from fundraising campaigns by organizations like Wikipedia. They often state something along the lines of, “If everyone who saw this message donated just $3, our fundraiser would be completed within an hour.”

The implication is that while most people don’t donate, if they did, even a small contribution could make a significant difference. The underlying assumption is that upon realizing they’re part of the non-donor majority, it’ll invoke a sense of responsibility or urgency to change the status quo, make a difference and avoid any the discomfort from not contributing.

In our study, participants were recruited through online platforms and asked to imagine receiving an email from FoodBank Plus+ stating, “A little girl in your neighborhood didn’t get breakfast. She may not get lunch either. We’re trying to help children get the healthy meals they need. Please consider making a donation.”

After this, we asked, “How much would you consider donating to this cause?” Participants were given four options: $10, $20, $40, or “I wouldn’t donate.”

Those in the social proof treatments got additional messaging stating,

- Social Proof – “Most people choose to donate $20.”

- Negative Social Proof – “Only a small fraction of people who read this message choose to give $20.”

What’d we find?

Neither the standard nor the negative social proof strategies resulted in higher donation rates nor amounts versus the control.

These results challenge widely held beliefs about the influence of social proof.

But our findings extend beyond this. Experiments are meaningless if we don’t dig deeper on why a given outcome occurred.

Following their donation decision, we asked participants to rate the level of pressure they felt during the process – i.e., “I felt pressured into selecting a specific amount of money to donate,” on a scale of 1 (not at all true) to 5 (very true).

Participants from both social proof conditions reported feeling significantly more pressure than those in the control condition. Additionally, we observed a negative correlation between the level of pressure felt and the donation amount. The higher the reported pressure, the lower the donation tended to be.

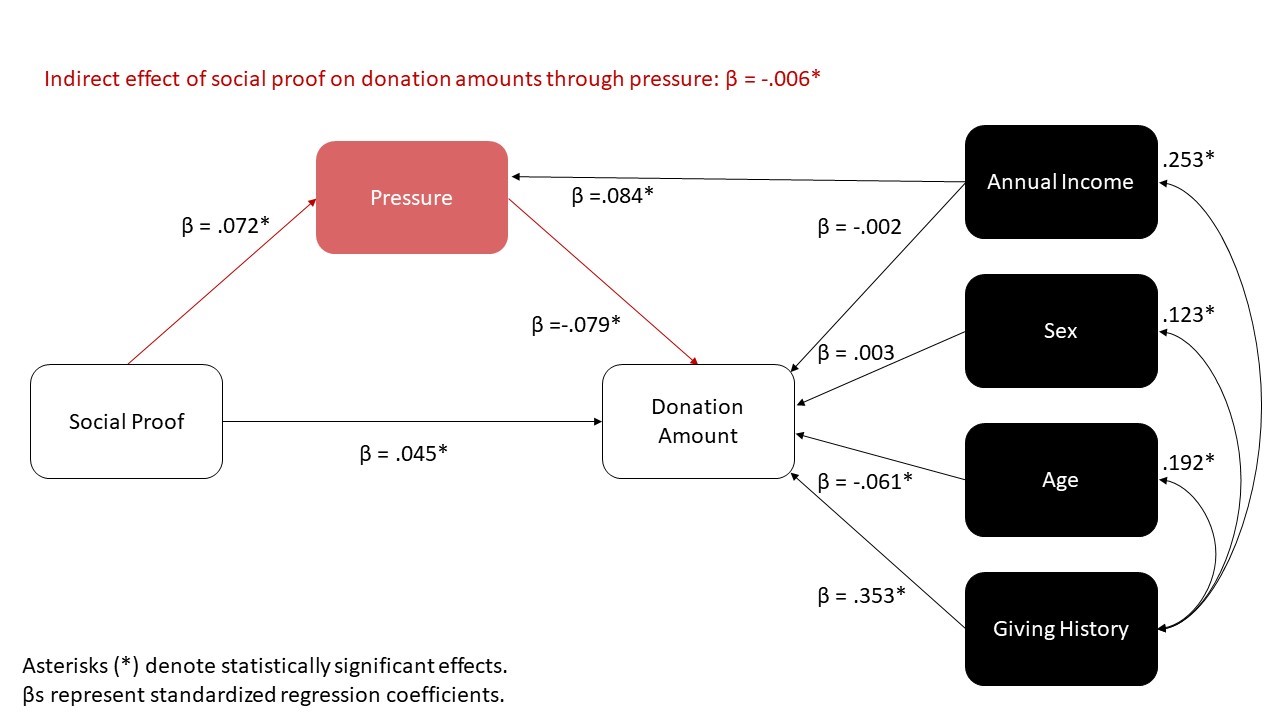

We synthesized our findings with a model to examine the direct and indirect effects of social proof and pressure on donation amount while controlling for demographics.

In line with our expectations participants in the social proof conditions tended to donate less when they felt pressured as noted by the red lines and pressure box.

However, the association between social proof and donation amounts became significantly positive when we account for feelings of pressure factor in pressure. This means if we remove the pressure, social proof can increase donations.

We call this a “suppression effect” with feelings of pressure suppressing or hiding the positive relationship between social proof and donation amounts. If you don’t measure pressure it incorrectly looks like social proof doesn’t work.

So, should you use social proof?

It’s not solely about employing the right nudges; understanding the psychological impact of these nudges is equally important. This calls for nuanced and empathetic communication that cites social proof while also respecting donor autonomy.

And context matters.

- If the audience you’re trying to get to support X aren’t already supportive of X then telling them that other people do it or that they’ll be judged poorly by those other people, or that those other people would want them to do it is mostly a waste of time.

- If whatever you’re asking the person to do is perceived as easy (e.g. low hassle, not time consuming, no risk assumed) then social proof is unnecessary and maybe even counter-productive.

That leaves a limited number of scenarios for using it. But here’s a for instance that jumps all the conditional hoops.

Asking a person to make a donation that is within their means but well above their historical average amount. Maybe it’s to become a monthly donor or ‘graduate’ to a higher status giving tier.

Signaling that other people in their situation elected to do this but only after carefully considering their individual situation is a test worth testing – i.e., supported by the evidence.

Drs. Kiki Koutmeridou and Stefano Di Domenico

If you found this post engaging, you might also appreciate:

Beware of Psychological Reactance

In Their Own Words: Satisfaction and Frustration in the Donor Experience

Should I Sustain or Should I Go Now? Stop Pressure Tactics

Nudging For (not “Or”) Donor Autonomy

Head spinning. Thank you! Terrific bottom line: “It’s not solely about employing the right nudges; understanding the psychological impact of these nudges is equally important. This calls for nuanced and empathetic communication that cites social proof while also respecting donor autonomy.”

Thanks Tom!

I agree with the bottom line though I wonder how people would have performed in real life with a real organization. It’s certainly worth testing.

Agree that we should retest this in the field.

Our field work shows donor autonomy matters a lot. Main findings are: (a) Donors dislike aggressive tactics that compromise their autonomy, (b) Autonomy boosts their commitment and intent to donate again, (c) More autonomy leads to more giving, and (d) Donor autonomy helps lower attrition rates.