The Easy Money is Gone: Overcoming Barriers to Growth

As I noted in the first post of this series —The Easy Money is Gone— a smaller pie and more mouths to feed is a recipe for disaster. And yet, status quo thinking, and activity dominate within organizations.

Fortunately, as reflected in the generous and thoughtful comments to that post there is optimism about the future –a belief that the growth curve can be bent upward — but only with a willingness to do business much differently.

Over the past 10 years I’ve worked with Kevin Schulman and the DonorVoice team researching hundreds of organizations, thousands and thousands of their donors and applying that research to effect fundamental change that leads to growth. In the series of posts that follows this one we’ll share approaches and techniques that I consider “breakthrough” in terms of breaking growth barriers.

But first, I think it helpful to share an overview of what we consider to be the principal barriers to growth. We’ve found that recognizing and dealing head-on with these barriers is essential for breaking out of the status quo.

Overcoming Barriers to Growth

In the realms of computer science, operations research and management science lives the world of mathematical optimization, conceptually a very simple concept, with the purpose of finding the best approach from a set of available alternatives.

This definition could just as easily be applied to fundraising strategy, and even life. There is however one insidious concern with optimization; what if the set of alternatives we are optimizing or choosing among is not complete? What if we have unintentionally omitted the best alternative from consideration? Unknowingly the “optimum” isn’t optimum at all, merely the best of our not- so- best options.

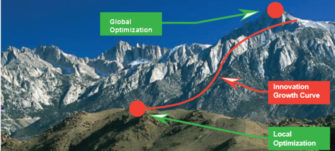

Mathematicians call this “local optimization” versus “global optimization” with the former representing identification of a “winner” among a set of choices that does not include the overall (or global) best choice.

This global versus local phenomenon is very useful when conceptually considering the lack of growth in non-profit fundraising and how to fix it.

Living in the Foothills

Nonprofit strategic planning, fundraising and marketing tend to live in the foothills. For a lot– dare I say “most” –of the big charities, they are locally optimized.

Within their conventional world of best practices–A/B testing of incremental changes, strategy by spreadsheet and internal white board sessions –their world is as good as it’s likely to get. In fact, the way to stay at the top of this locally optimized place is to stop the incremental changes since they only cause the organization to slip (albeit a small amount) from the locally optimized perch at the top of the foothill when you factor in all the time and cost and the reality that for every “winning”, campaign level test there are far more losing ones. And every losing idea that wasn’t ‘breakthrough’ or innovative in the first-place costs money; both hard cost and opportunity cost.

Characteristics of Organizations Living in the Foothills.

There are three categories of organizational characteristics – mindset, methods, metrics – to describe a nonprofit that is running its business in the foothills. Similarly, these same categories can be applied to describe and distinguish “foothill groups’ from the very few living (or at least climbing) on the mountain peaks.

Mindset

- No theory or point of view on how world works

- Territorial or zero-sum mentality among staff and partners

- Accepts status quo

- Thinks doing same thing in a new channel (for example, adding ‘online’ or ‘social’ in addition to the direct mail channel) is innovation

- Senior leadership is not demanding change

- Is interested in new as long as it is proven

- Ignores the leaky bucket of attrition and invests little or nothing in retention

- Believes donors are born, not created

Methods

- Treats channel as strategy

- A/B testing of incremental changes

- Only uses transactional data; ignores donor attitudinal data

- Focused on correlation, not causation

- Efficiency over effectiveness

- Strategy by spreadsheet

- Tomorrow’s plan looks like yesterday’s

- Organized by functional area

- Using same old team or replaces existing team with clone of the old

- Internally generated ideas

Metrics

- Campaign level. E.g. Year-end appeal, annual fund, annual renewal campaigns

- Highest Previous Contribution, Most Recent Contribution

- Response rate viewed as highly important

- Average gift used as a basic measure of success

Strategy as a Key Characteristic of a Foothill Organization

Look no further than how strategy is typically thought of as the (not so) shining example of local optimization and the need for change.

Strategy for the nonprofit living in the foothills quickly devolves into a spreadsheet exercise. The larger the spreadsheets, the more confident the local optimization organization is in its process. All those numbers and data feel analytical, even scientific.

So why do managers and those on the front lines responsible for executing the “strategy” tend to dread the annual strategic planning ritual? Why does it consume so much time and have so little impact on organizational actions? The reason: those people responsible for delivering on the plan recognize the process as it exists today does not produce novel strategies.

Instead, it perpetuates the status quo.

But, if the alternative is ideation sessions and off-site retreats to come up with radical, big new ideas then these same managers and directors make the right choice in sticking with the process that at least produces some short-term comfort versus the 1 day of talking with no action.

The short-term comfort (along with a certain amount of resignation) lasts until the returns start coming in and we see – to nobody’s actual surprise – that revenue is not as predictable as Excel would lead us to believe – though the costs are dead on.

Strategy Hallmarks of a Globally Optimized/Growing Organization

So, what is the alternative? What does strategy look like if an organization is attempting to globally optimize its world? For starters,

- Strategy is about forcing a choice, stating what the organization is and is not doing.

- It is about making assumptions and explicit choices and outlining both – BRIEFLY – in 1 page, 2 maxima.

- If your strategy document is more than 2 pages, then there is a 99.9% it isn’t a strategy at all. It is a planning and forecasting and prognosticating exercise to deliver short-term comfort. It is also almost certainly a document that looks radically similar to last year’s.

- A strategy is clear, concise and focused. Just like good copy.

- Strategy is about making small bets with the explicit choices made and not made and the associated assumptions spelled out.

- With a solid articulation of the 2 (or 3 max) choices available to solve a problem (e.g. falling retention rates, lousy uptake with monthly giving offer) or achieve a goal and equally solid articulation of the assumptions that must be true for either choice to work then we increase our chance of success.

- Evaluate those assumptions and determine which set best fits with what you do well, is most likely to be true and then make a choice. This will greatly increase chances of success.

- Increasing our chance of success is not the same as reducing risk

- It is about turning left or right and not believing we can do both at the same time.

- It is about monitoring performance of the small bet and modifying course or abandoning it all together.

- Contrary to popular wisdom, strategy is not about first failing a whole lot. That is called “failing”.

- If there is no risk, there is no strategy. If you feel comfortable, there is no a strategy.

Organizations that accept the status quo are highly limited in their potential to move to the peaks. The real mental or cultural barrier is not assigning risk to status quo, which for most nonprofits is a flat to downward trendline on net growth.

If this trendline is implicitly accepted then any process, product or thinking that deviates from the current order is seen as riskier than doing nothing different and the implied risk level of zero assigned to it. It is easy to see why change is unlikely in these organizations.

Characteristics of Organizations Headed For, or Already Living on the Peaks.

Here are the principal characteristics we’ve discovered in those organizations that are poised for growth or are growing.

Mindset

- Realizes big change is only scary if it ignores risk of status quo

- Creating mindset that status quo is not ok

- Fears the organization is living in foothills

- Looks for subject matter experts, not “turn-key” generalists

- Is continually demanding better and better

- Knows strategy is about turning left OR right

Method

- Lets donor needs dictate strategy

- Getting out of incremental testing business

- Developing hypotheses

- Links attitudinal data to transactional

- Separates “what we think” from “what we know”

- Builds teams who are not zero-sum thinkers

- Realizes “big” change is only seen as ”big” from the foothills

- Moves quickly

- Collects and acts on donor feedback at key interaction points

Metrics

- Steers by longer term metrics like Lifetime Value

- Understands the dangers and limitation campaign level focus

- Lives and acts by leading not lagging indicators. ( Donor Commitment/Loyalty is a leading indicator; RFM a lagging indicator

Organizations must start looking at the forest instead of the trees by recognizing events that are unfolding (e.g. response rates dropping, acquisition costs going up, mobile phone usage, changing demographics) are interrelated parts of a pattern that is occurring over time. As a short hand rubric organizations can assess whether they are climbing or even capable of it by placing themselves on the following continuum of thinking:

Methods

This is a catch all for methodologies, processes and approaches to doing business. There are too many examples and too much detail for me to be expansive in this post. Therefore, what follows is a non-exhaustive, summary list of Methods for the global optimization organization. We’ll get into detail with example in the next posts in this series.

- Collecting attitudinal data to answer questions of need, motive and preference.

- Data linkage to connect attitudinal data to transactional for holistic models

- Adding “voice of the donor” feedback loops to events/interactions and using that feedback to dictate mitigation and upsell/cross-sell opportunities.

- Hypothesis testing instead of random “mining” for correlations, which exist in abundance with most being meaningless

- Separating budget from strategy.

- Having strategy that involves more risk because it challenges the status quo. (By this definition most organizations aren’t doing strategy at all).

- Reorganizing based on donor needsand real segments (versus internally derived ‘segments’ that add no value to the donor or the organization) instead of organizing around internal, functional area of expertise

- Kill the annual budget process and replace it with rolling forecasts. The former takes far more time, is too expensive and detailed, doesn’t contribute significantly to overall strategy of the organization, stifles innovation, demotivates staff, and promotes unethical behavior by driving people “to meet the numbers at almost any cost.”

- Shifting to best-in-breed, subject matter experts instead of “full-service” and “turn-key” agencies.

Want to Make the Climb?

So where does this leave us? What are the strategies for thinking about local versus global optimization? Here are three alternatives. They are mutually exclusive and require the organization to climb fast, slow or not at all. The choices presented allow for only one choice to be made.

- Head Down

- Reduce cost/headcount

- Few tests/no tests

- Raise average gift marginally

This strategy is about being cost effective while deciding to stay locally optimized. Roughly half the nonprofit market fits here. This is not an indictment or judgment, merely the recognition of the reality that Lake Wobegon “where all the children are above average” does not exist in the nonprofit world.

- Finger in the Air

- Lead with method

- Let in-market change drive mindset change

- Skunk-works pilot projects with the likely small number of staff willing to press for something meaningfully different.

Approximately one-third of the market will or should make this choice. It is a slower climb but a climb toward the peak nonetheless.

- Climb Mountain

- Team is on board or prepared to change (quickly)

- Raising expectations

- Status quo is not acceptable

- Have big goals

- Right leadership team in place (likely a new team)

What path will you choose?

Roger

P.S. Kevin and I explore this set of issues in greater detail in an article in New York University’s Philanthropy Journal. You’ll find it here.