The Right Kind of Donor Motivation

Emotionally manipulative messages can backfire because of psychological reactance, that rebellious response people sometimes show when they feel unduly pressured. They may still give in the moment but your donor retention hinges on your ability to create a sense of autonomy in your donors.

But how to do that? And can it be measured and understood? And is there really a difference in behavior tied to type of motivation?

It’s intuitive that motivation varies in amount: People can be more or less motivated to donate. And, of course, fundraisers want to increase people’s motivation to donate. Many fundraisers operate under the assumption that more donor motivation, however it’s produced, will yield more successful campaigns.

However, motivation doesn’t just vary in its quantity. There are, in fact, different qualities of motivation—specifically, autonomous and controlled motivation. What’s more, motivation science indicates the type of motivation is generally more important than amount in predicting important aspects of human behavior.

Autonomous motivation involves acting with a sense of volition and choice. It’s the type of motivation your donors feel when they grasp the importance of the work your charity does and genuinely want to support it. Note, this doesn’t mean you dump a lot of information on this donor. It means you’ve put your mission in front of a prospect who was already interested (e.g., marketing conservation to a conservationist) or you’ve conveyed the significance of your work in a manner that enables your prospect to want to help its work.

Controlled motivation involves acting with a sense of pressure and obligation. It’s the type of motivation your donors feel when they’re guilted into giving or when they feel like they should give because it’s socially expected. In other words, autonomously motivated giving arises from donors’ internal willingness, controlled giving is compelled by external, situational factors (e.g., that telemarketer that just won’t let it go) or by uncomfortable feelings (e.g., that guilt you’re made to feel when the DRTV spot shows pictures of crying, starving children).

Which type of donor motivation would you guess is associated with donor satisfaction and longer-term commitment?

Since the late 1970s, hundreds of experimental and field studies have examined the correlates and outcomes of autonomous and controlled motivation. These studies have spanned many domains including, parenting, education, healthcare, work, sport, and psychotherapy. Consistently, autonomous qualities of motivation yield advantages in performance, enhanced persistence and commitment, and greater psychological well-being.

These results aren’t difficult to grasp, even on an intuitive level. When people feel like they really want to put themselves into a course of action—be it a medication schedule, an exercise regime, an educational program, or a new workplace initiative—it’s no wonder they’re able to stick with it and do a better job.

To provide a quick demonstration of how autonomous and controlled motivation are related to fundraising, we conducted a brief survey study. The participants reported giving to a food bank or soup kitchen in the last year. Using a survey we measured the qualities and type of motivation that prompted the giving. This is another example of zero-party data, that rarified, uber important data that is willingly and voluntarily supplied by your donors.

This isn’t measurement for measurement’s sake. Measuring motivation is the only way to know if your newsletter or appeal or overall donor journey is delivering the right or wrong kind of motivation.

Of course, there is an indirect measure that doesn’t require you to do anything: Attrition rate. Just sit back, wait for the reams of people to stop giving and you can safely assume a lot of them lacked the right kind of motivation.

Autonomous motivation was measured with items like, “I donate because I strongly value the work the food charity does” and “Giving to that food charity is personally meaningful for me.” Controlled motivation was measured with items like, “I donate because giving to charity is viewed positive by society,” “I feel pressured by others to give,” and “It’s what a good person should do.”

We also measured donors’ amotivation, which refers to a lack of motivation. Amotivation is contrasted with both autonomous and controlled motivation because it connotes a lack of intention to act. When people are amotivated, it’s generally because they either feel incapable or because they don’t see a particular course of action as being relevant for them. Amotivation was measured with items like, “I donate because… Honestly, I don’t know why” and “I’m not sure; it was a random decision.”

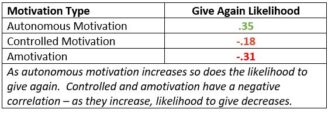

What did we find? A strong pattern and relationship between the right and wrong type of motivation and giving.

So, how can fundraisers promote autonomous motivation among their donors? This is a question that’s been asked and answered in the psychological literature.

The complete answer merits its own post but the short answer is simple: Support your donors’ feelings of self-governance. To make this all more concrete, let’s review some copy from an email I just received—one of the many COVID-19 appeals that have been flooding my inbox lately.

The very first sentence immediately tries to induce fear and sympathy. It’s emotionally manipulative. The fact that most people have received, by now, dozens of appeals just like this just puts the manipulation into sharper relief.

That second line in red, bold, emergency underlined font? Very pressuring with the implication that if you don’t donate, it could cost the lives of the world’s most vulnerable children and families. Something like this might cross the prospects mind: Is this factually correct? Aren’t studies showing that children are at the lowest risk of dying from COVID-19? Is there some particular reason why this COVID-19 solicitation is mentioning children? I don’t see it.

If we don’t reach them, they could pay the ultimate price. More pressure. It’s not only controlling, it’s starting to get really boring.

As a result of COVID-19, we could face famine in many countries… The first informative sentence, finally! Unfortunately, it’s squandered by more controlling copy in the rest of the paragraph.

It’s unthinkable. – Oh I see. If you get me to agree with this statement, I’ll have to swallow the rest of your manipulation to be consistent. I don’t think so.

Please will you help? Asking directly for help is okay, but there’s usually room to convey respect for people’s abilities to choose to want to fulfill your request. Better would be something like: Would you like to help?

We understand what a difficult time this is for many people… BUT

The sincerity of this sentence is immediately undermined with another ask. Compounding matters, the request conveys valuable information about how people’s donations could have had a positive, informational impact if only it had been relayed on its own.

Please don’t delay. One last dose of external pressure for good measure, I guess.

Now, let’s imagine this appeal re-worked with the principles we’ve covered in this post. It might look something like this:

Dear XXXX,

As a result of COVID-19, people in many countries could face famine. We’re asking people to donate money to help provide children with food.

You can choose to donate any amount you wish. To put things into perspective for you, $45.90 could supply a food parcel for three months in some areas.

We understand if you’re unable to donate at this time. COVID-19 has affected many people and you too may be going through a difficult time.

If you wish to donate, you can do so by clicking the following link.

You can also learn more about our work by clicking here.

We wish you and your loved ones all the best.

Thank you for your time.

Sincerely,

XXXX

Can you see how these solicitations are very different?

We’ll be delving more deeply into this topic in the future. For now, I hope you find the distinction between autonomous and controlled motivation illuminating.

Stefano

References

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guildford Press

I get this but does the autonomous version sound too casual – does it lack urgency for an emergency ask for example?

Rupert, this was, first and foremost, a quick illustration to juxtapose with the one that actually went out, not an attempt at our version of final. Urgency might suggest when I should do something but not why I should do something. The fundraising copy we’ve been linguistically and empirically scoring is, on average, horrific at narrative. What does that have to do with your question? Narrative is storytelling and done well, it lights up the same parts of the brain as if you actually experienced it. Imagine for a moment if you could teleport your prospective donors to the emergency for 5 minutes? If they actually lived it, bore direct witness you wouldn’t need to tell them it was urgent, you wouldn’t need to yell it or do damn near anything and conversion would be 100%. Your best bet at replicating this is showing people (versus telling) what’s going on. if done well it will be as if they are experiencing it themselves. Fundraising copy – based on objective, grounded, evidence based scoring – is all tell, no show. Telling is by its very essence, controlling.

Hi Rupert, Thanks for sharing your thoughts.

Like Kevin said a little earlier, the modification wasn’t intended as a final copy. It was mostly intended as a demonstration of how different the original could be once all the controlling elements are removed.

If we were tasked with really developing an autonomy-supportive message, we’d work a number of elements into it, apart from removing all controlling aspects. For example, we’d showcase those elements of the charity that donors would be most likely interested and concerned about (we’d know from our zero-party data and other useful avenues) and we’d offer solid rationales for the charity’s work and for its ask. This would amplify the message’s *salience* without making it controlling. Having a clear meaningful rationale that’s aligned with people’s interests and concerns is autonomy-supportive. I agree that the copy in the post is a little too causal–hopefully it doesn’t detract from the main point of the post.

Excellent article ! Very insightful ! Thank you !

Thanks, Dana! Much appreciated.

Thanks, Dana! Much appreciated!

I can see one immediate difference between the two sets of appeal copy: while the first one is, I agree, extremely guilt-trippy, the second one completely sucks.

In its desire to remove any kind of controlled motivation, it removes any emotional triggers at all, including the ones that might prompt autonomous motivation. It’s vague: ‘people in many countries’, ‘in some areas’.

It’s potentially confusing – a ‘find out more’ straight after a give link.

It doesn’t speak positively to the donor’s values at all.

No way should someone send that as an appeal. There is definitely a way to write an appeal that would promote autonomous motivation. But that ain’t it.

Adrian, thanks for reading, subscribing and challenging. A few thoughts and I expect Stefano will reply as well.

It may well ‘suck’ though seems we can agree it isn’t controlling and we know for certain that sucks if one actually cares about delivering a profit to the charity. This example was never intended to be ‘final’ copy in anyway, shape or form, mostly a juxtaposition to the one that actually went out to a bazillion people. The one we’d hit the ‘send’ button on would go through more refinements. That said, it’s instructive to pick apart the critique.

1) “it removes any emotional triggers at all?”

a. What is an emotional trigger?

b. What does that mean, specifically?

c. Here is more science around emotion: Emotions do not cause giving. Emotions are the goal, not the cause. Said differently, if you think you add an ‘emotional trigger” to cause someone to give then you are, at best, only half correct in understanding giving behavior. People don’t give because you made them feel sad, they give because they think it will make them feel happy (if indeed, your copy succeeded in creating a ‘sad’ emotional trigger).

2) It doesn’t speak positively to the donor’s values?

a Perhaps. But, again, how would you know?

b. What values? All of them? Some of them? How do you define and measure these and is it the same for everybody?

c. What isn’t reflected here but is part of our broader practice at DonorVoice is measuring Identities, each of which has it’s own set of values and goals. In this way, values and goals aren’t universal, they are Identity and context and donor specific.

Again, this wasn’t intended to be sent ‘as is’, it was mere illustration. If it were, we’d have far greater likelihood of ‘speaking to their values’ if we actually had a clue what those were, which would be part of any DonorVoice copy going out the door to a donor.

C’mon Adrian, tell us what you really think!

I’m kidding. I appreciate the colorful feedback.

I think I addressed much of your criticism in my other replies (particularly in my reply to Larissa).

But I want to elaborate on something Kevin picked out. This notion of “emotional trigger.” Terms like these often reflect an underlying idea that the goal is to essentially manipulate people into giving — press their emotional buttons as if donors are machines that could be flipped on into give mode. They’re not, obviously.

Emotionally evocative language can be okay when it helps make the importance of the charity’s work more salient and meaningful to donors — after all, prospective donors won’t give if your message doesn’t orient their attention. And sometimes, very strong emotions can be conveyed without the messages being pressuring or controlling, especially when they’re an organic part of the charity’s mission (e.g., charities fighting against egregious abuses of human rights).

When the goal is to support people’s autonomous motivation for giving to a cause, the strategy becomes about presenting material in a way that allows donors to grasp the significance of your charity and align with its cause; recognizing donors as people who *actively* make choices about how they direct their time and money rather than automatons that get passively cued up and directed by whatever’s in front of them.

Thank you for this Stefano – super interesting! What are your thoughts on empathy language: “Imagine only having enough to feed your child one meal a day…” or “Imagine not knowing where your next meal would come from. What would you do?” (thinking of that email above). Where would that type of language fall? Is that a bit of manipulation or is empathy language bringing the donor to a sense of the importance of the gift and its impact?

Larissa, we can pick up on this more when we speak to review the copy optimizer results. Until then, here are a few thoughts to your very good question. There is a big difference between empathy and sympathy. The latter is feeling sad, which as I noted in an earlier reply to Adrian, is only useful if we convey (directly or indirectly) that giving will make them feel not sad.

Empathy is our ability to understand other people’s feelings as if we were having them ourselves. That is really powerful for creating a connection. However, the best way to do this is with the narrative form – see reply on storytelling above. Telling a story that shows (not tells) the mother/child situation is the most powerful way to create empathy. After telling the story, the writer of the letter might them say, “As a father/mother, I can’t imagine how hard that must be, can you?” But, this is more of an involving dimension to the letter (which we know drives response) than an empathy building one.

Hi Larissa! Great question. Building on Kevin’s earlier response, I’d say that whether or not a particular phrase is controlling or autonomy-supportive depends on the larger context. We generally don’t advise against particular sentences or images on an a priori. Instead, we examine the overall frame/context of the message and try to optimize/modify on the basis of how those elements relate the “gestalt.”