Nudging For (not “Or”) Donor Autonomy

In a recent Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly article, Rebecca Ruehle and colleagues considered some of the ethical objections raised against nudge techniques promoting charitable giving. The authors argued nudges are morally ok even when they violate donor autonomy, if they’re aimed at issues they deem morally worth it e.g. disaster recovery, clean drinking water, and hunger prevention.

DonorVoice isn’t the fundraising ethics committee nor did we stay at a Holiday Inn last night…

We’re the behavioral science fundraising agency and so our point of view is that Ruehle and colleagues miss a key fact: Donor autonomy is necessary—repeat: Necessary!—for optimal fundraising for all causes. Fostering a sense of autonomy creates high quality motivation, which is the gift that keeps on giving (literally).

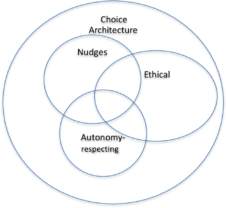

Fundraisers and ethicists alike should make donor autonomy the first behavioral science priority as the best nudges are those that enhance autonomous decision making.

Nudges

Nudging has become commonplace. Default options, for example, are now part and parcel of most donation widgets: the option to give monthly is often pre-selected and prospective donors are more likely to indicate monthly donations at the point of sign-up, sometimes even unknowingly.

Ruehle and colleagues point out that nudges can undermine donor autonomy in at least three ways:

First, nudges may not be as easily resistible as they seem and thus violate freedom of choice. Second, they manipulatively bypass or pervert people’s reflective capacities and shape people’s preferences “behind their backs” or “in the dark” and thus violate agency. Third, they may inhibit the extent to which people achieve their own goals and be the author of their lives and thus thwart self-constitution [which the authors define as someone’s identity and self-chosen goals].

We agree with their assessment here and reckon anyone who has taken the time to read open-text comments from donors on why they cancel would too. Statements like, I didn’t know I signed up for monthly donations, It wasn’t my intention to give monthly, and I felt pressured to give monthly even though I didn’t want to are all too common.

Ruehle and colleagues explore some of the nuances between nudging techniques and donor autonomy. They articulate many points with which we agree. For example, they state that “Charities … should not chug or emotionally blackmail people into donating there and then, as this constitutes an infringement on their autonomy. Take the use of emotionally disturbing pictures or other ways of guilt tripping.” We’ve made similar assertions.

Ruehle and colleagues explore some of the nuances between nudging techniques and donor autonomy. They articulate many points with which we agree. For example, they state that “Charities … should not chug or emotionally blackmail people into donating there and then, as this constitutes an infringement on their autonomy. Take the use of emotionally disturbing pictures or other ways of guilt tripping.” We’ve made similar assertions.

However, Ruehl and colleague ultimately conclude that nudge techniques, though potentially problematic for autonomy, are sometimes justified if the behavioral outcome is of high moral worth. We disagree, not from an ethical perspective (ethics isn’t our concern here), but from a behavioral science perspective.

Over 50 years of research in motivational science—both basic research conducted in laboratory and field settings and applied research conducted in real-world domains—indicates that self-determination or “autonomy” is of paramount importance for optimal engagement. As an aside, nudge theory began to really come into its own in the early 2000s but the psychological science of autonomy stretches back to the late 1970s. As nudge practitioners continue to enmesh themselves into the applied realm of fundraising, they will increasingly need to integrate autonomy as a foundational psychological need with immense motivational import.

Why is autonomy important? Because motivation comes in two basic qualities—autonomous motivation and controlled motivation. When donors are autonomously motivated, they support a charitable cause because they personally understand and value it. They’re more likely to commit to the cause and they genuinely want to support it because doing so is a way for them to enact and share their values. Autonomously motivated giving is satisfying for donors and it’s giving that lasts.

However, when donors are controlled in their motivation, they give because they feel pressured. Those pressures can take the form of a pushy canvasser or telemarketer, a guilt-trippy solicitation, or even internal pressures that put their self-worth on the line (“If I don’t support this charity, I’m a bad person”). Donors who are controlled in their motivations may offer support but that support is unlikely to last.

Perhaps worse, they’re more likely to resent the fundraising organization. Social norming, default options, decoys, and other nudge techniques run the risk of leaving donors feeling manipulated and controlled in their giving: “Oh, I see, other people gave this much eh [social norming], so if I don’t give at least that much, it must mean I’m a bad person…”

Given the motivational significance of autonomy, we believe it’s never okay—from a fundraising perspective—to thwart donor autonomy for running a nudge. You might even say that the higher the moral worth of a campaign, the greater the responsibility of the fundraiser to provide donors with opportunities for autonomous decision making.

Having said all this, it’s important to point out that nudging isn’t antithetical to autonomy. Ruehle and colleagues point this out very nicely when they state, “[Nudges] can enhance—instead of bypass or subvert—people’s reflective decision-making capacities. Given that people will pay more attention to and more easily digest information presented in personalized, accessible, salient, and emotionally laden ways, their resulting decisions will be more informed and autonomous.” We at DonorVoice agree.

Stefano

P.S. Here are the article details, Ruehle, R. C., Engelen, B., & Archer, A. (2021). Nudging charitable giving: What (if anything) is wrong with it? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 50(2), 353-371.